Of the many natural hazards in Africa, mushrooms are not necessarily the first thing to spring to mind. But Neil van der Reij, a mushroom researcher with the Department of Agriculture and Environmental Affairs, is quoted as saying mushroom poisoning is “common” in South Africa (1).

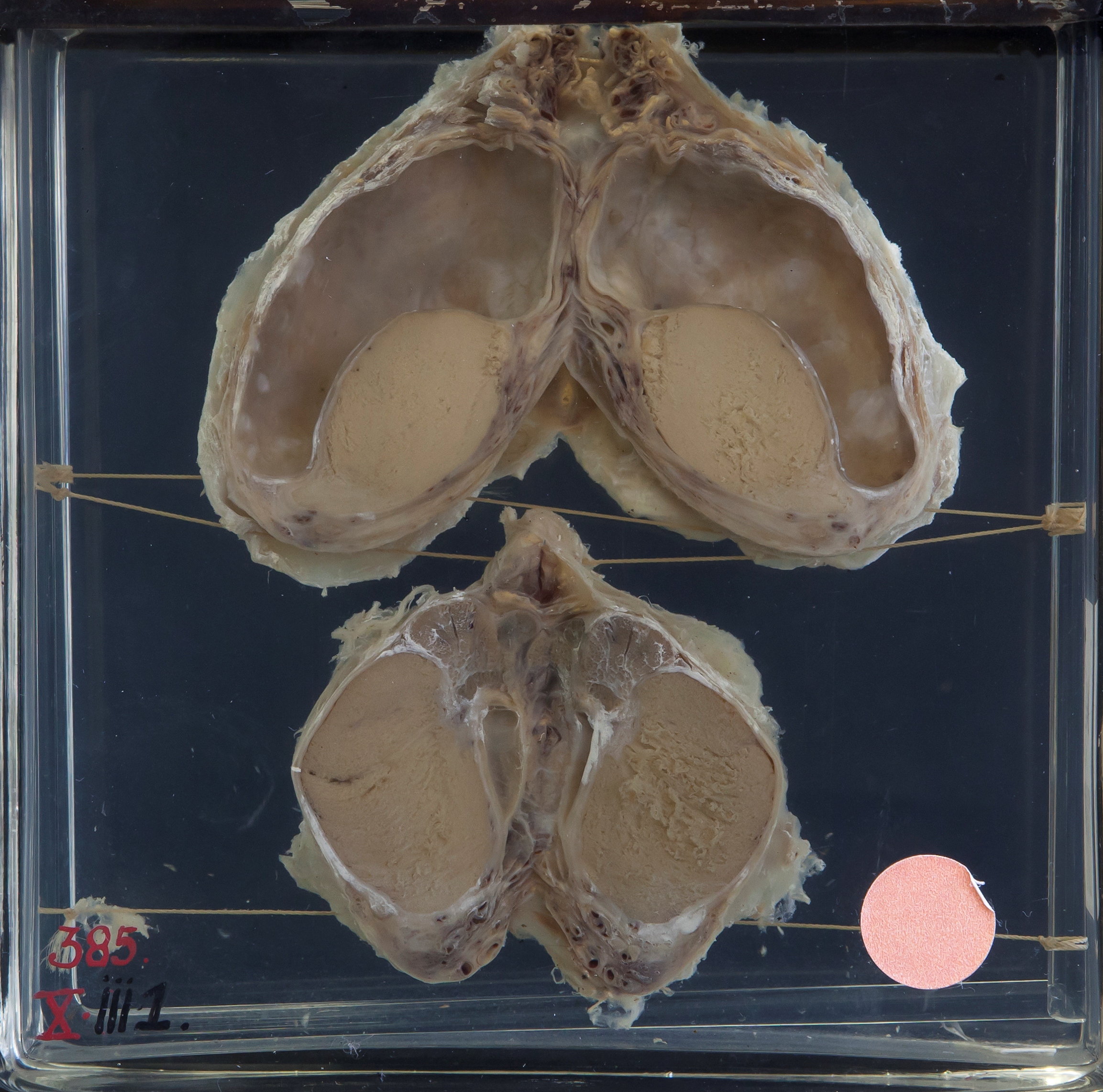

In our collection we have two liver specimens titled “mushroom poisoning”. Each case is noted to be “one of a whole family who were poisoned by eating mushrooms”. The incident occurred in Cape Town in May of 1927.

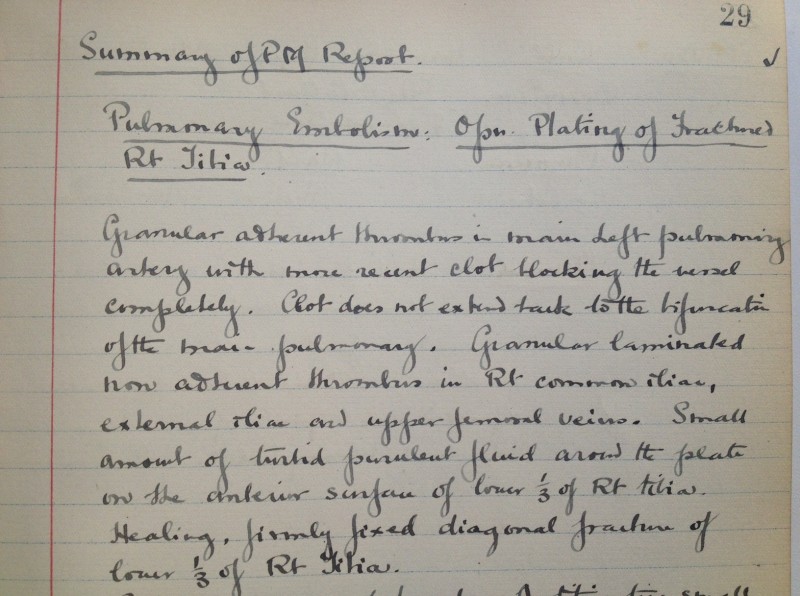

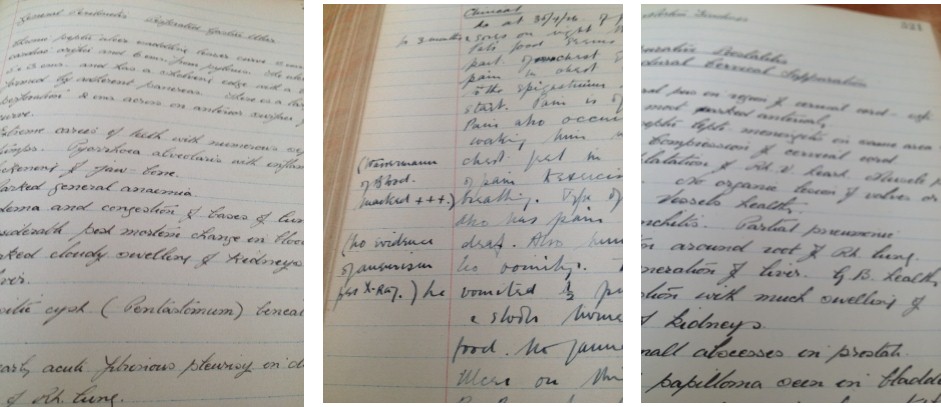

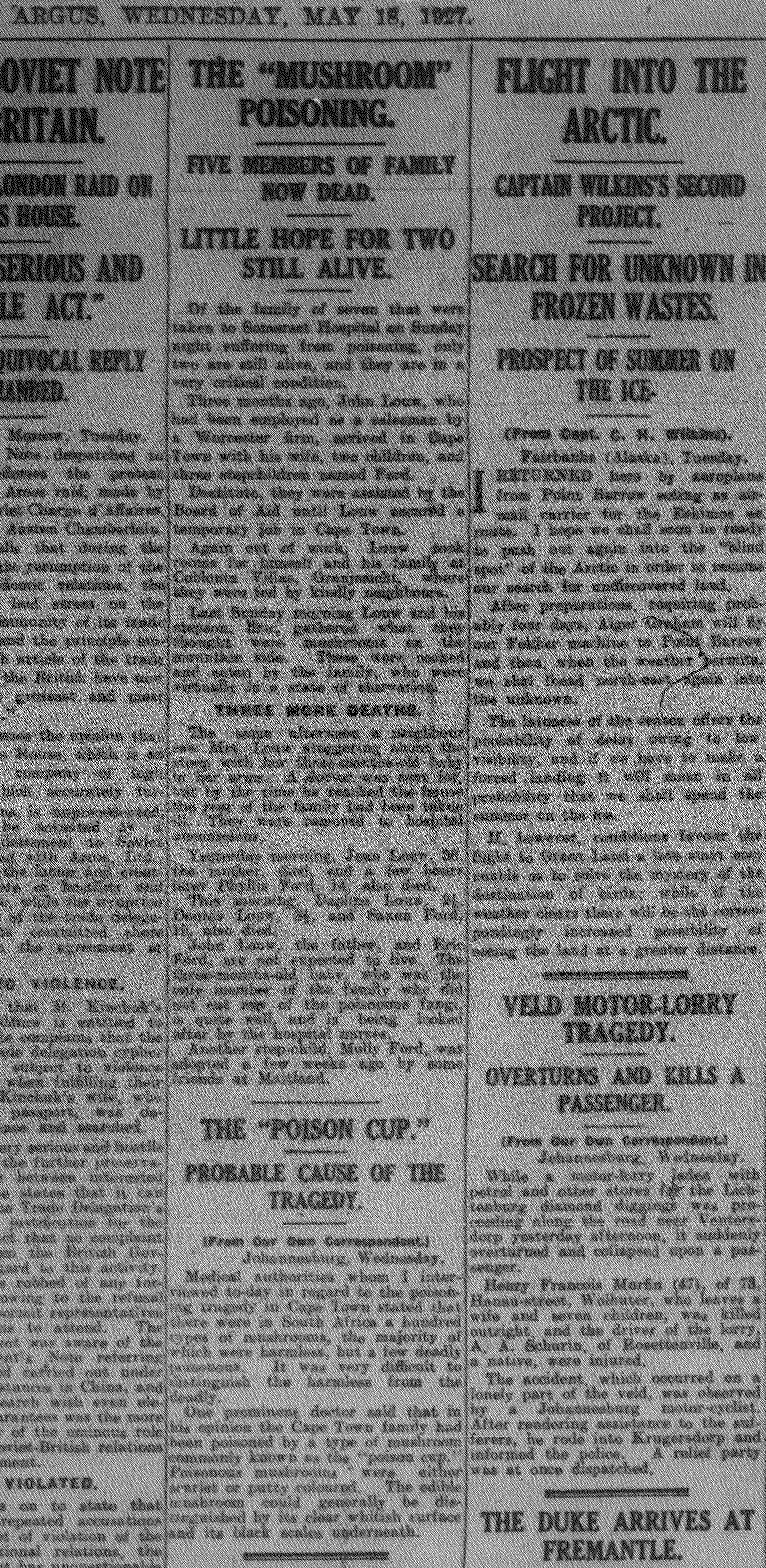

The original post-mortem reports add minimal non-pathological details, so over the Christmas period I took the time to browse the archive of the The Cape Argus for more about the story. Sure enough, a report appeared on 16 May, the day after the the entire family was admitted to Somerset Hospital. Subsequent updates documented the deaths of first the mother, followed by five children aged 2 to 14 years, then the father, and finally the 18-year-old stepson on May 19. According to the paper, the destitute family had recently arrived in Cape Town and were staying in a boarding house. Apparently they were relying on the kindness of neighbours for food. One Sunday morning the father and his elder stepson climbed the foothills of Table Mountain above the city, where they found mushrooms – it appeared these were eaten after being boiled, and symptoms set in after only a few hours. At post-mortem, the pathology was primarily fatty degeneration of the liver, kidneys and heart, resulting in multi-organ failure. The only family members to survive were the 3-month-old baby and a little girl who had been adopted by friends a few weeks before the incident.

Of all the cases in our collection, why do these resonate particularly? Aside from being terribly sad events, there is something fascinating about natural poisoning whether by snakes, arachnids, plants or funghi. My quick search of the web found media accounts of 16 fatal cases of mushroom poisoning (in 5 clusters) in South Africa between 2008 and 2014. In addition, in 2001 a child poisoned by mushrooms was saved by a liver transplant at Red Cross Children’s Hospital, but her grandfather succumbed (2). Going back 100 years, it is part of Southern Cape history that the prominent businessman who founded the village of Wilderness died there as a consequence of eating mushrooms he had collected locally; his sister and a guest succumbed too (3). Medical reports can be found in the SAMJ archive: In 1955, five of nine related patients died in Ermelo, and in 1988, four of five patients died in the Ciskei after apparently sharing a single mushroom (4,5).

One wonders how many other cases go unrecognised.

Frustratingly, only the more recent end of the SAMJ archive is searchable, but by chance I discovered that a report of our own mushroom poisoning cases was published in November 1927 by Mervish and Silberbauer (well known Cape doctors), including the post mortem notes of Prof JB Ryrie (6). They conclude their paper with an account of experiments they conducted on a frog heart and rabbit intestine, using the vomitus of the patients.

There is a pattern to these poisoning incidents; they all involve clusters of family and sometimes extend to friends as well, because a meal, with or without mushrooms, is usually shared. Also in common is that all the incidents were known or assumed to have involved Amanita phalloides, and the course to death was agonising. In the Cape, mushroom poisonings mostly occur in April/May, while in the rest of the country they occur during the months of summer rainfall. The 2016 mushroom season in Cape Town is now open for those of us who dare forage!

See also

www.pathologylearningcentre.uct.ac.za/harmful-substances-fungi

SOURCES

- http://www.iol.co.za/news/south-africa/kwazulu-natal/mushroom-poisoning-common-in-sa-1390479

- http://www.iol.co.za/news/south-africa/poisoned-girl-gets-christmas-gift-of-life-78523

- http://www.georgeherald.com/news/News/General/162148/Centenary-of-poison-mushroom-deaths

- Steyn DG, Steyn DW, Van der Westhuizen GC, Louwrens BA. Mushroom poisoning. S Afr Med J. 1956; 30:885-890

- Rivett MJ, Boon GP. Mushroom (Amanita phalloides) poisoning in the Ciskei. S Afr Med J. 1988;73:317.

- Silberbauer SF, Mervish L. Notes on cases of fungus poisoning. J Med Assoc S Afr. 1927; 1(21): 549-553

Dedicated to my colleague, friend and mushroom guide, DRH.