At 30 years old my mother had a radical mastectomy, meaning her left breast was removed along with the chest wall muscle underneath, and the lymph nodes under her left arm. Years later as a medical student I learned that she had not needed this extreme surgery. But back then the distinctions between types and stages of breast cancer were still being worked out, and my mother and her surgeon opted not to take any chances.

The mutilating operation changed the course of her life. She also underwent some form of ovarian ablation (her ovaries were rendered non-functional so that they produced no hormones which might stimulate the cancer to grow.) This brought on early menopause, further adding to the negative effects on her physical health and psyche.

Ten years after the breast surgery she complained of chest pain and a cough. Her chest X-ray showed a “white-out”, a blizzard obliterating both of her lungs. As I remember it, the possibilities were lymphangitis carcinomatosa (indicating cancer finely spread throughout the lungs), bird fancier’s lung (an allergic reaction to her parrot), tuberculosis (a chronic bacterial infection) or sarcoidosis (an inflammatory disease with no known cause). She had a bronchoscopy (for which she refused anaesthesia or sedation) and the biopsy sample was compatible with TB or sarcoidosis, since they have a very similar appearance under the microscope. Because tuberculosis is rife in South Africa, she was started on a course of anti-tuberculous drugs, which made her very unwell. The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was a brand new form of testing back then, but training as a virologist I was able to arrange a PCR to detect Mycobacteria tuberculosis in the biopsy tissue, which proved negative. Her treatment was changed to the only available option for sarcoidosis, which was high dose prednisone. She fought to have the dose reduced to a level where the side-effects were tolerable. After more than a decade of treatment the disease seemed to “burn out”, leaving her with lung fibrosis (scarring) and bronchiectasis (dilated airways).

By now, in her 50s, her skeleton had become dangerously osteoporotic (brittle), this because of the long-term prednisone treatment and premature menopause. Attention turned to her bone density and a number of drugs were tried to improve it, but all of them induced problematic side effects.

In her late 60’s chest symptoms occurred again, and a right-sided pleural effusion (fluid between the lung and the chest wall) was found. This needed repeated drainage and finally the pleural space was simply eliminated by fusing the lung to the chest wall, using a chemical irritant. By now she also had signs of pulmonary hypertension and cor pulmonale (right heart failure), and required a pace-maker for atrial fibrillation (heart flutter).

At age 73 the final event was sudden. Overnight she became desperately ill, and in the emergency unit her oxygen saturation was low. Laboratory tests showed that her acute pneumonia was caused by parainfluenza-3 virus, a virus usually seen in very young children. She required high flow oxygen in intensive care and was given massive doses of cortisone to try to prevent further inflammation in her lungs. She sank into delirium with a steroid psychosis. Already weakened by pulmonary cachexia (wasting), she stopped eating and then drinking.

Cause of death on on her death certificate was “end-stage lung disease”. I don’t recall if sarcoidosis was specifically mentioned.

At most, 1 in 20 people diagnosed with sarcoidosis will die of the disease, usually of respiratory failure. Although the inflammatory response in sarcoidosis has been well studied, the actual cause of the disease remains unknown. Aside from the lungs, it commonly involves lymph nodes, skin and liver, and less often other organs such as the heart and eyes.

The full story of any disease is really only known through personal experience of it.

There are lots of old, stock descriptive terms that still appear in modern pathology texts – I’m thinking of things like “anchovy sauce” to describe the contents of an

There are lots of old, stock descriptive terms that still appear in modern pathology texts – I’m thinking of things like “anchovy sauce” to describe the contents of an  Continuing the theme but changing the topic, it could be time to reconsider the term “miliary” tuberculosis. Miliary tuberculosis occurs when a shower of blood-borne bacteria result in numerous tiny, white tuberculous foci in the organs, evidently resembling millet seeds. Now millet is not your run-of-the-mill grain these days, though students from rural Africa or India would be acquainted with it. For urban youth a grain like quinoa is more on trend, or perhaps sesame seed is more widely known, and both are much the same thing as millet visually. But the point is, when you have to explain what millet is, surely it’s no longer useful as an analogy.

Continuing the theme but changing the topic, it could be time to reconsider the term “miliary” tuberculosis. Miliary tuberculosis occurs when a shower of blood-borne bacteria result in numerous tiny, white tuberculous foci in the organs, evidently resembling millet seeds. Now millet is not your run-of-the-mill grain these days, though students from rural Africa or India would be acquainted with it. For urban youth a grain like quinoa is more on trend, or perhaps sesame seed is more widely known, and both are much the same thing as millet visually. But the point is, when you have to explain what millet is, surely it’s no longer useful as an analogy.

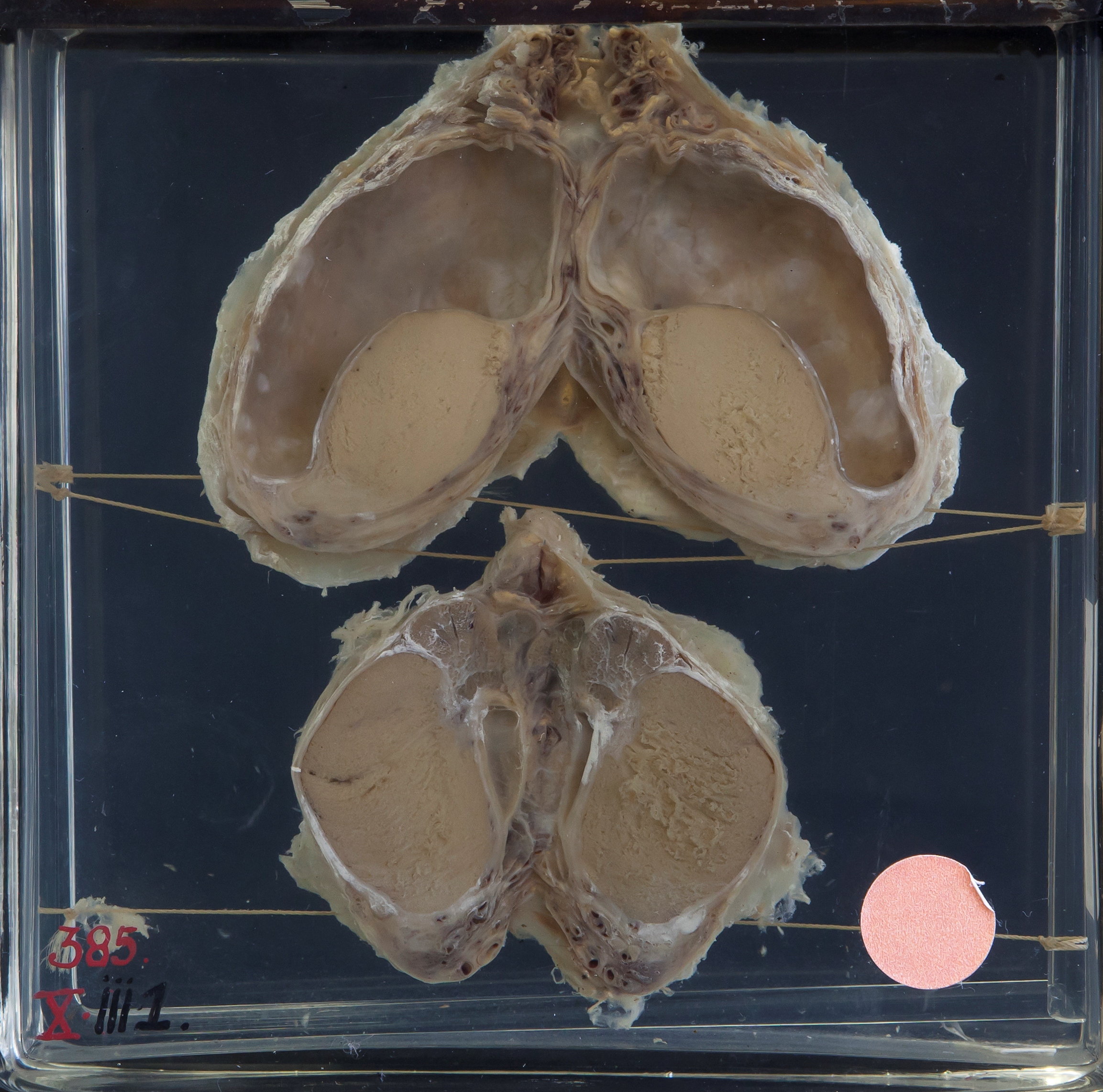

Moving on to “nutmeg liver”, a mottled appearance the liver may have when it is chronically congested, for example in heart failure. Because nutmeg was used “medicinally” through the centuries, physicians would once have known its appearance as well as their cooks did. Only someone who grates their own nutmeg will understand the nutmeg liver analogy because it refers to the appearance of a whole nutmeg in cross section. The description is no longer helpful in a modern urban world where nutmeg will almost always be bought in a convenient powdered state, ready for sprinkling.

Moving on to “nutmeg liver”, a mottled appearance the liver may have when it is chronically congested, for example in heart failure. Because nutmeg was used “medicinally” through the centuries, physicians would once have known its appearance as well as their cooks did. Only someone who grates their own nutmeg will understand the nutmeg liver analogy because it refers to the appearance of a whole nutmeg in cross section. The description is no longer helpful in a modern urban world where nutmeg will almost always be bought in a convenient powdered state, ready for sprinkling.

![Sites of brown adipose tissue in adult humans, as revealed by PET scanning. [Image credit: Professor Jan Nedergaard, The Wenner-Gren Institute,The Arrhenius Labs, Stockholm University]](http://digipathblog.files.wordpress.com/2013/06/brown-fat-distribution-nedergaard-e1370609910305.jpg?w=300)