by Alan G Morris

Alan G. Morris is Professor Emeritus in the Department of Human Biology at the University of Cape Town. He also serves as a Council Member of Historical Publications South Africa.

One book a year doesn’t sound like much for a publisher, but when you have been running for 104 years, this amounts to lot of shelf space. The Van Riebeeck Society (VRS) changed its name in 2019 to Historical Publications South Africa (HiPSA) and adopted a broader perspective.

The overall objective is still the same: to make accessible rare books from the past and previously unpublished documents and diaries relating to the history of Southern Africa.

I am a physical anthropologist with an interest in the peopling of southern Africa over the last ten thousand years or so. Most of my research has been on the bony remains of long dead people, but it was never possible for me to study ‘bodies’ without a social and archaeological context to the individuals. This led me right from the start to read the reports of travelers in southern Africa who first met the descendants of the people whose skeletons I studied in the archaeological record. For me, the place I found many of the early traveler’s reports was in the pages of the VRS and the first one I read was the journal of Hendrik Jacob Wikar, published by the VRS in 1935[1].

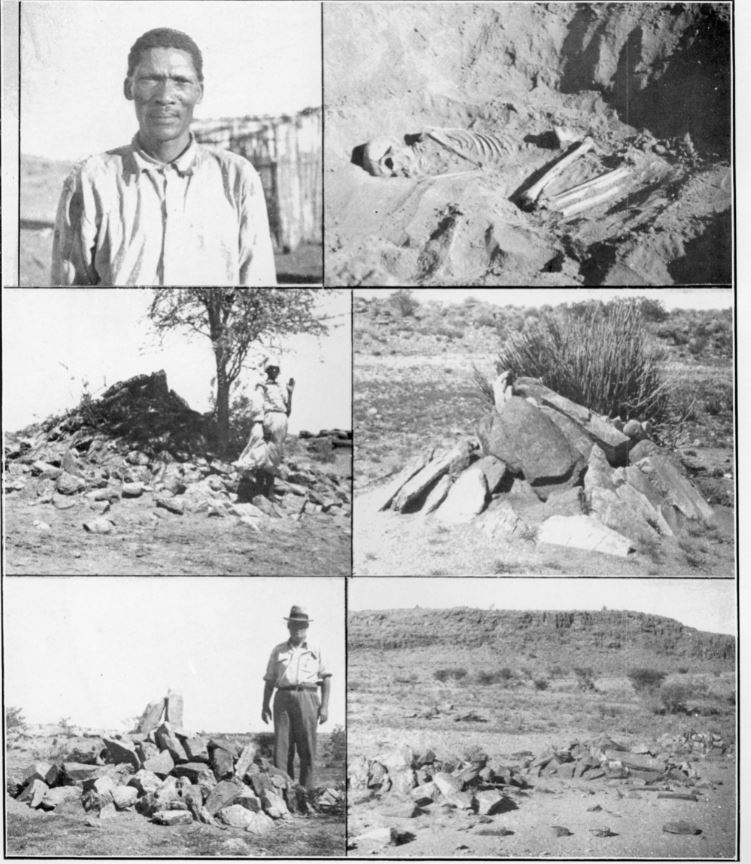

I was busy trying to understand why Professor T.F. Dreyer and his young colleague A.J.D. Meiring of the Grey University College in Bloemfontein decided to travel along the Orange River from Augrabies Falls to Upington and excavate old graves from the river alluvium. In the space of three weeks starting in June 1936, the two of them with the help of three labourers from the National Museum in Bloemfontein dug up 112 graves and accessioned 69 human skeletons to the museum collection[2].

Why did they dig there, and who were the people whose graves they were disturbing?

I only had scrappy field notes from their expedition, but they did publish one short paper that described a few of the graves[3]. It was in the published paper that I found reference to Wikar’s journal.

Dreyer and Meiring had been amongst the first readers of the new VRS publication, and it was Wikar’s description of the Khoekhoe people along the Orange (Gariep) River that had impressed them. Their plan was to dig up graves in the locations where Wikar mentioned meeting ‘pure Hottentots’.

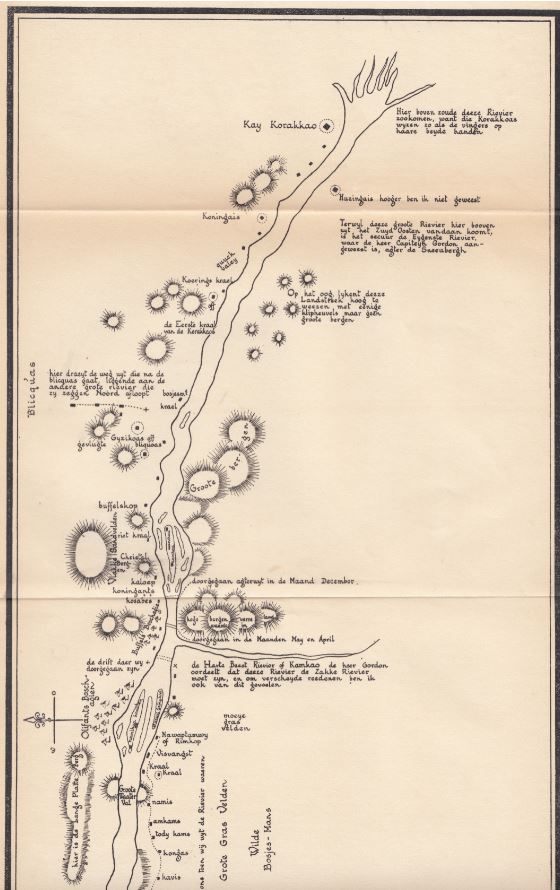

I borrowed the UCT African Studies Library copy of Wikar and entered the world of early traveller’s reports. It was an important experience for me because I had to learn how to read between the lines in the publication. The account by Dreyer and Meiring was confusing, and it was clear that they were interpreting what Wikar had seen.[4] Mossop, the editor, provided a thorough historical background to the Dutch civil servant Wikar. Most important was the fact that Wikar was desperately trying to get into the good books of Governor van Plettenberg by providing the most detailed description of the people and places along the Gariep. Wikar had gotten himself into a gambling debt and had deserted the employ of the Dutch East India Company and fled the Colony to avoid his creditors. In the end, he spent four years between 1775 and 1779 travelling beyond the colonial frontier with the only hope of readmittance being a pardon from Governor van Plettenberg.

The people who Wikar had seen were essentially unacculturated Khoekhoe whom he described from his knowledge of the Khoekhoe of the Cape whom he had met in Cape Town. The ethnographic information from Wikar has turned out to be quite accurate including descriptions of burial ceremonies that fit perfectly with the archaeological evidence.

Over the years that I worked on my PhD and afterward, I learned how to stitch data together from anatomy, archaeology, social anthropology and most importantly, from history. Wikar’s journal was not the only HiPSA/VRS volume I devoured. There were some very early Dutch descriptions of the Khoesan (First Series No.14), the travels of the Swedes Spaarman (Second Series No.6/7) and Thunberg (Second Series No.17), the English Doctor William Somerville (Second Series No.10), and the important observations of the Frenchman Le Vaillant (Second Series No.38 and Third Series No.3).

View the Catalogue of Publications by VRS / HiPSA

What the century long editors of HiPSA/VRS provided for me was a rich documentary of peoples and places seen through the eyes of the first literate Europeans to explore southern Africa. But the Khoesan have not always been simply objects of study. Two literate Khoekhoe leaders left documents that the HiPSA/VRS publishers have translated from the original Dutch. The journal of Hendrik Witbooi of Namibia (First Series No.9) and the records of the Griqua Kapteins of Philippolis (Second Series No.25) give a voice in their own words to historical detail unfiltered by Colonial Europeans.

Perhaps the hardest voice to hear in any kind of investigation is that of the San foragers who existed throughout the Karoo and Northern Cape. A new avenue of investigation through DNA has helped a great deal, but one of the upcoming HiPSA volumes is promising to give us a new perspective of one of the saddest events of South African History – the genocide of the Cape San. During the 1860s, Louis Anthing reported the atrocities perpetrated by European and Baster farmers on the /Xam San of the northern Karoo and Bushmanland. Although my studies had looked at these same people in the two or three centuries before the incursion of the Europeans, this new work soon to be published by HiPSA is a record of their end. Not a happy volume, but one that will resonate with the many thousands of Khoesan descendants who are part of our modern South African mosaic.

A full list of HiPSA publications can be found here.

The work produced by VRS / HiPSA has been the result of over a century of scholarly dedication and commitment to sharing substantive, relevant unpublished archival materials. Why not think about becoming a member and supporting their ongoing work? Learn more here.

References

[1] Mossop, E.E. (ed.) 1935. The Journal of Hendrik Jacob Wikar (1779). Cape Town: Van Riebeeck Society, First Series No.15.

[2] Morris, AG (1995) The Einiqua: an analysis of the Kakamas skeletons. In: Einiqualand: Studies of the Orange River Frontier. ed. A.B. Smith. p.110-164. Cape Town: University of Cape Town Press.

[3] Dreyer, T.F. & Meiring, A.J.D. (1937) A preliminary report on an expedition to collect old Hottentot skulls. Soologie Navorsing van die Nasionale Museum, Bloemfontein 1(7):81-88.

[4] Morris, AG (2022) Bones and Bodies: How South African scientists studied race. Johannesburg: Wits Press.