by Beverley Angus, African Studies Librarian, Special Collections

Every death is like the burning of a library – Alex Haley

2021 began very badly

After almost a year of working from home, isolating, and cancelling a trip to visit my family in Scotland, a very close friend, Kathy, was admitted to hospital on the 4th of January with COVID and died on the 21st of January. After three weeks of hope, it was a devastating blow.

My retirement, beckoning at the end of 2021, no longer looked so bright. I had already missed out on a year of interaction with researchers and colleagues, something I particularly enjoyed as a reference librarian for African Studies in Special Collections.

Learn more about my 2020 lockdown experience.

____________ ______________

And COVID was not yet done with us.

By March 2021, following the second wave of the pandemic in South Africa, staff were allowed back into Jagger Library to organise scans and book transfers for researchers and postgraduate students beginning the new academic year. I was rostered for the week of 12th April. It was good to be assisting researchers and postgraduates with material they could source nowhere else and seeing some of my colleagues in the flesh.

The images below are some of the last to be taken in the Reading Room in November 2020.

Jagger Library was a beautiful, if not very practical, building restored to its former glory in 2012. A scholarly location which provided its users with a quiet and inspiring environment supported by librarians and archivists, willing to assist where they could. But it was the content that was its greatest treasure.

The African Studies Library had been built up over decades by librarians who had wanted the collection to include texts from all over the African continent including publications in indigenous languages. A vast collection of sources, both academic and ephemeral, had been acquired and we, in 2021, continued the tradition of pro-active collecting.

Sunday the 18th of April dawned hot…

The air itself warm on the skin. A small plume of smoke had been visible on Devil’s Peak from early morning and on my way to Fish Hoek, the smoke from the fire was travelling towards False Bay, driven by a westerly wind. We had endured strong south easterly winds all summer, and this fire held no forebodings for me. But from the beach we witnessed the smoke getting darker and more intense. The warm wind began gusting strongly, strewing food containers and belongings around.

I had heard that the Rhodes Memorial Restaurant had burnt down and thought of my dear friend whose ashes we had sprinkled there, but then horrific images started popping up on social media – photos of Jagger Library on fire, the windows on the plaza filled with bright red and orange flames. Surely photoshopped and fake news, and in very poor taste.

Then other reports started coming in, and the terrible truth could no longer be denied. It was incomprehensible to me that my place of work for nearly 30 years was a pile of ashes. Not just the building, but most of the contents of the African Studies Library, a library nurtured for over 70 years by generations of librarians. It was so hard to accept that this world class research collection had actually been destroyed in such a short space of time.

The destruction of the Jagger Library caught the attention of both local and international media. Writing in the Daily Maverick on the 24th of April, Lwando Xaso outlined the shock of losing a beloved library:

Crying over books, in light of the human loss we have experienced this past year, seems misplaced. But it is particularly devastating at this time because it is not something that seemed to be an imminent threat. We have been so vigilant in keeping ourselves safe from a virus that worrying about a fire devastating the lives of so many people and burning down a historic library seemed too remote, too cruel and beyond the bandwidth of what we can take.

At this stage we had no idea what, or even if, anything had survived the inferno. For three days we talked to each other online in counselling sessions – and cried. I was overcome, like others, by this chance happening when the neighbouring buildings were unscathed. We all tried to understand how the fire had penetrated the building and why it had to be Jagger Library that had been affected.

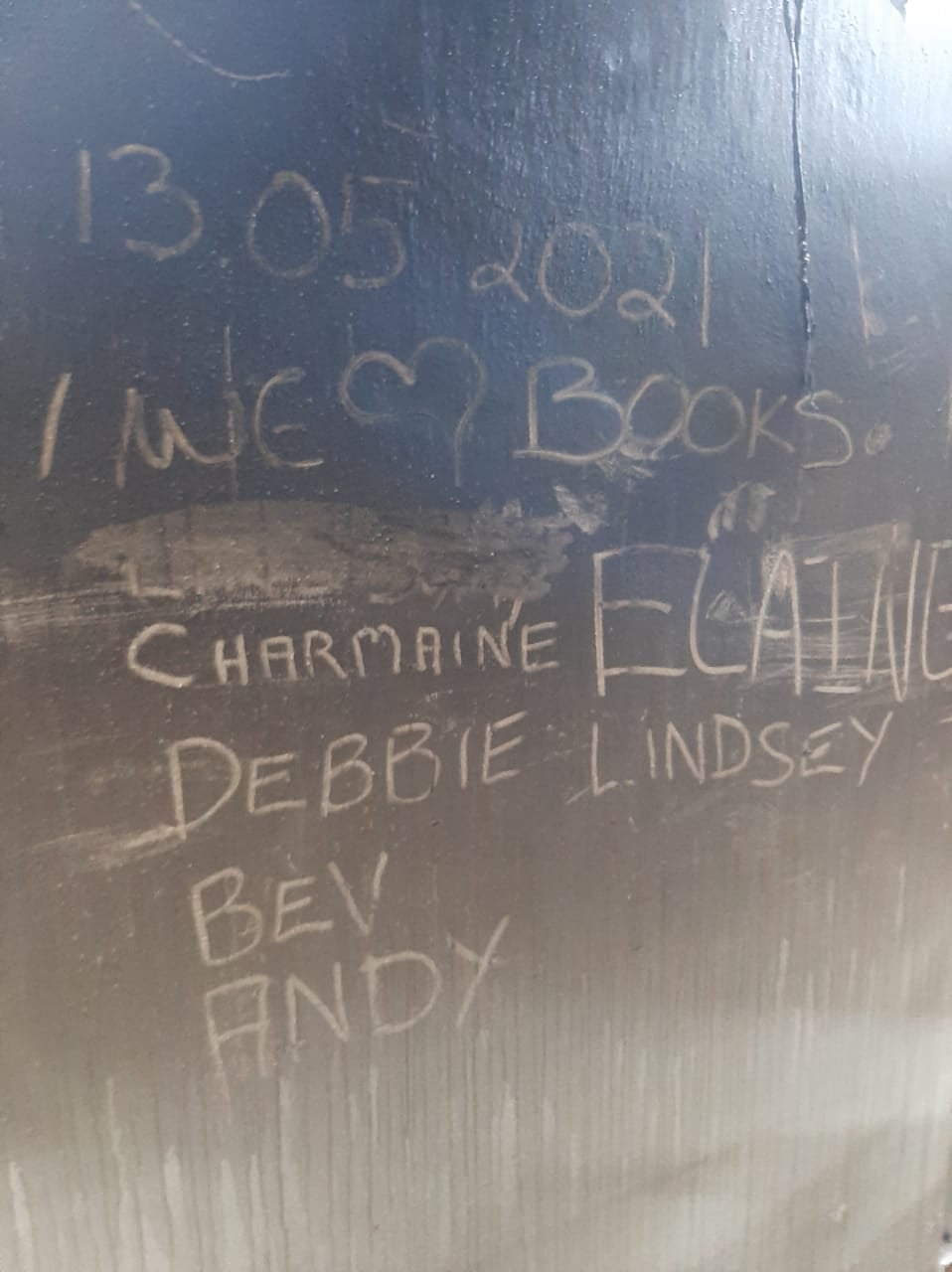

It all felt so very personal – not just because as a librarian, I had assisted so many researchers over the years – but also because I had helped to develop the collection through the purchase of print material working with Sue Ogterop, Allegra Louw, Busi Khangala, Margie Struthers, Colin Darch, Belinda Southgate, and Sandy Shell, and particularly because I had taken sole responsibility for the African Studies Film Collection when Sue retired in 2014. I loved identifying titles for the collection, tracking them down, writing synopses and, especially, recommending them to academics for lectures and students to complement their research. Film is such a powerful medium and can portray so vividly situations and attitudes in a way print cannot do. It was a phenomenal collection started by Sue in the 1980s. By April 2021, the collection comprised some 3500 titles including many classics and other films which had taken much persistence to acquire.

Until access was granted to the site on the following Tuesday, I held onto the tiny scrap of hope that the room in which the DVD collection was housed, might have survived the fire. But, in fact, it burnt fiercely, being made up of discs, plastic cases and paper covers. So much lost, much of which will be hard and costly to replace. It was absolutely heart breaking, like losing a child I had nurtured for over 20 years.

Being a person who needs to be busy to cope with stress and distress, I was relieved to be told that we could report to campus on Thursday, 22nd April, to begin the salvage effort. This was the beginning of a physical four-week project which thankfully allowed little time to grieve and left me so exhausted at the end of the day that I slept soundly each night, rising each morning to face a new day, fuelled by adrenaline and as the day proceeded, by numerous cups of free coffee.

Wearing hard hats and masks, we started late Thursday afternoon in the archive store in dark, humid and wet conditions working in teams to crate the boxes of manuscripts in an orderly notarised manner. The first bit of good news was that, although there was some water damage, this area had survived the flames. Volunteers created human chains to move material out of the building to storage.

This continued through the weekend and when the crane began lifting the twisted steel girders off what had once been the roof, we moved into the audio-visual archive one level down with access from a side entrance. The water had been waist-deep in this area where old film formats such as Betacam and VHS tapes were stored. Having been its guardian for a period, I felt personally attached to this collection and glad to be part of its retrieval. Here it was even darker, more humid, and airless and the material had to be ferried up four ramps by the human conveyor belt consisting of both UCT Libraries’ staff and volunteers.

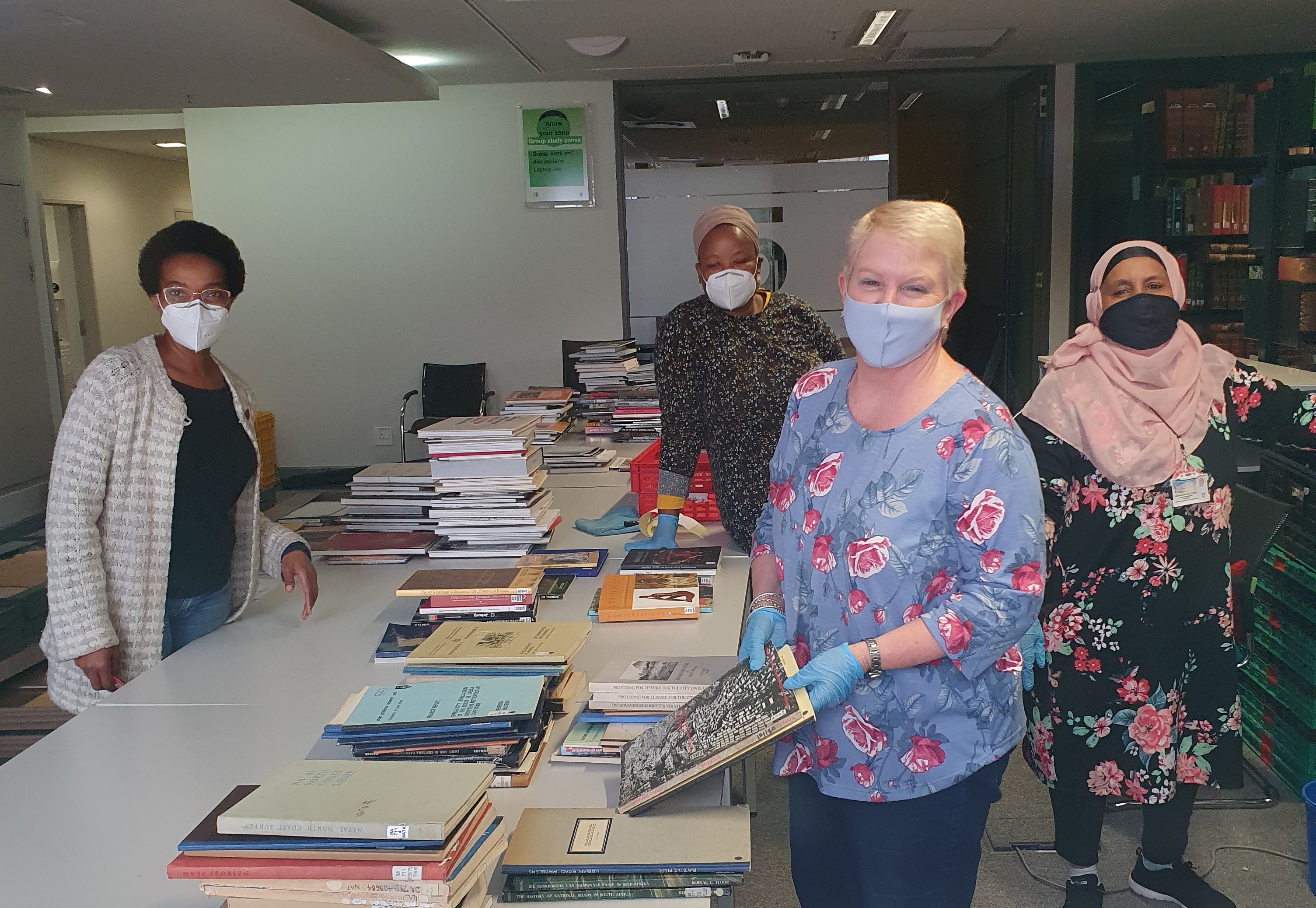

We took turns to work in the dungeon, on the ramps, and outside to keep going. This became a little overwhelming for me after a few days and I transferred to a location (Library Learning Lounge) where Rare Books, Government Publications and African Studies material was being transported for storage.

Hundreds of crates would arrive by truck and had to be directed to different spaces for unpacking and storage. Those volunteers and human chains again were indispensable. It was hectic as the crates needed to be emptied as soon as possible for re-use. Supervising the activities was also exhausting. As a librarian I was not used to talking ALL day (besides having to make spur of the moment decisions). Some of the material in this area was moved numerous times to allow for more and more salvaged stock.

It was heartening to see what had survived.

Keeping busy was the antidote to grief and I continued to work in other areas re-organising crates of manuscript boxes; in the stacks behind the reading room containing African language and history books where conditions were difficult as the location, three weeks on, was mouldy, smelly, and airless and the space was not suited to accommodating so many bodies and crates at one time. Books had to be moved up a winding narrow staircase to a lift. It was exhilarating to retrieve as many items as we did from an area that had miraculously survived the flames. The following week we moved up a level to the journal stack, where we had to contend, not just with water damage, but with walls and publications covered in soot.

By this time, I realised effort equalled hope and that the road to recovery was crammed with people willing to put in that effort – managers and colleagues who had stepped out of their comfort zones to deal calmly with the daily myriad challenges presented by this disaster, but still arrived every morning cheerful and optimistic.

And volunteers – young and old, alumni, academics, retired staff, and the public – who came back time and time again because they just wanted to help, considering it an honour. In the face of their cheerful enthusiasm, one had no choice but to put on one’s happy face and crack on.

Claire, who, at the age of 79, was present almost every day, heaving crates and moving books; Cameron, a student of physics, who energetically took over the repacking of hundreds of pamphlet boxes into different crates for storage; Joshua Pirie (JP), a quietly spoken third year engineering student, who became my right-hand man on a difficult day, and took charge of students whose attention kept straying from the job at hand and, the Sea Cadets, a group of delightful, disciplined teenage boys and young men in blue, who spent a Saturday providing muscle and energy – and called me Mam.

In the face of all this energy and hope, I found new depths of strength, both mental and physical, to carry on. I was a valuable member of a community that had lost its home but not its spirit.

Then there were the messages of condolence and support from academics and researchers who had consulted both published and primary material in Special Collections, and wanted us to know just how important, not only the library, but also the assistance of the librarians and archivists has been to them; how much they valued the space, the people, and the material.

We lost so much but every item saved has helped to lift my spirits. Taking stock of the thousands of publications, posters and maps that survived and working alongside my colleagues in this phase of recovery, has also been healing. There is a lot of work still to be done but it no longer seems quite so daunting, so impossible. I no longer feel so helpless or so hopeless.

Like Jagger Library, life is fragile. I will always miss my friend but her lessons of love, tolerance and what it means to be the very best grandmother, will always stay with me. We should always mourn the loss of Jagger and the African print material consumed by the fire, but it cannot be undone and, while initially I felt I had lost my professional identity with the loss of Jagger, I have come to realise that I am still that person and can use my experience to rebuild. Covid and the fire have emphasised the uncertainties of life but, like others, I have found the resilience to withstand the twofold tragedy…and move forward.

Tragedy should be used as a source of strength. No matter the difficulties or how painful the experience, if we lose hope, that’s the real disaster – Dalai Lama XIV