My name is Alex D’Angelo, and I have been a librarian at UCT for more than a quarter of a century.

I remember when the Jagger reading room was stripped of its tatty 1970s additions, and institutional green carpet, and worn-out tubular-steel chairs, and put back to the way it had been when it was first built as a reading room in the 1930s. It was beautiful.

It got its polished corkwood floors back, and the walls went back to the original paint, painstakingly identified, under layers of institutional gloss. They rebuilt the reference desk and the long refectory tables, and the airy galleries reaching up three levels to a vaulted ceiling.

Every year, we’d take students and parents through the modern, cutting-edge library, with its glass and electronics, and the clinical efficiency of a bank, until at last they reached this reading room.

And I would watch them thinking, pretty much universally “Ah. Now this is what I was expecting from a university library.”

And we’d give them the spiel, about how this was just the reading room, and the African writers were on the shelves in the galleries running around above us, and how the unique, unpublished, collections went down, level after level, climate controlled, humidity controlled, because we were holding them in readiness for all the generations yet to come.

And then we’d talk about what was in the holdings, about material from all over Africa, collected on special buying trips, and struggle posters, and samizdat, and the far older, world heritage, material, like the Protestant “Burned Bible” that survived the Inquisition’s fires, or the 1471 history, off the old Gutenberg press, that was itself a reprint of a 1st Century A.D. Roman textbook, still in use all those centuries later, or the first edition of old Tom Payne’s “Rights of Man”, 1791 – hot off the press from Revolutionary France.

And then, late one day, in a very few hours, Jagger went up in flames.

And when it was cool enough, we went in to save our stock.

The reading room and galleries were gone, but the basements remained. Unburned, but wet from the fire hoses.

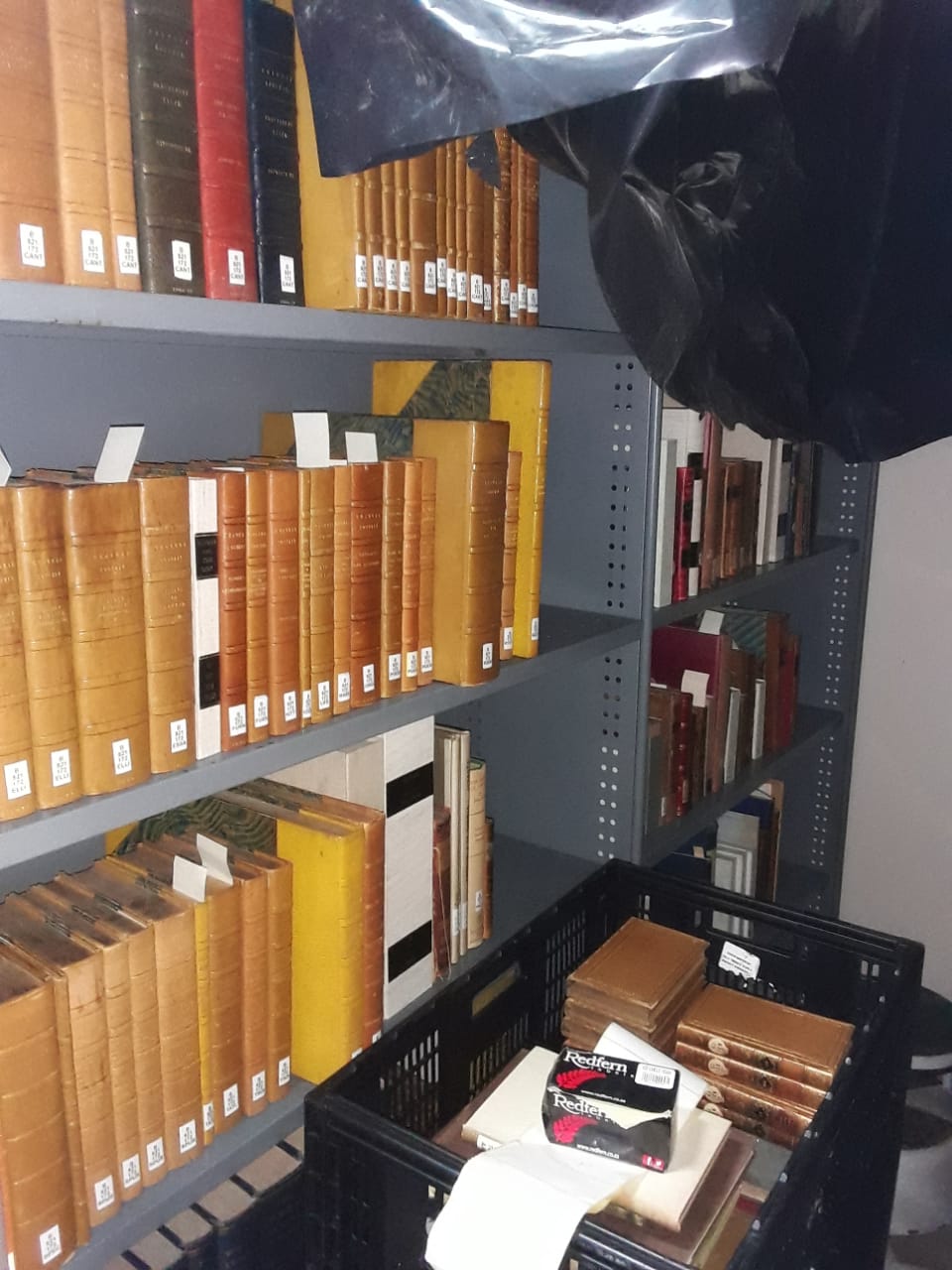

So from the day we were granted permission to enter the building, we hauled crates out of the narrow alleys between the stacks of compactus units, one row at a time, because that’s how compactus shelving works, under the wreck of Jagger, burrowing under plastic sheets that were stretched to keep the endlessly dripping water off the stock, by torch light, with electricians struggling to run power to the pumps and fans, to dry out the water that kept sloshing and squelching underfoot.

We were in a hurry because damp stock gets mouldy in an eyeblink. Spores love book glues, leather bindings, and thick, creamy, Eighteenth Century book paper. Book spores have really good taste.

If it was wet, we froze it. Crate after crate, in giant refrigerated trucks. Freezing stops mould until we can dry the books under forced air.

Every so often we’d come up for air and look at each other, sheeted in sweat, T-shirts soaked and clinging to us, eyes wide and staring, and go back down again.

I attended a Faculty Board between haulage shifts and gave them a garbled word salad.

But a lot of it was safe. Most of it was unharmed. Slowly this became clear as we got the worst out.

And later it got easier. The light was reliable. There was forced air blowing in. We could peel black the plastic sheets when the trickling stopped. We developed efficiencies of movement and of tasks. We had enough crates.

There was just a massive quantity to move.

Thank God for the lines of volunteers. Hundreds of people. Whole lines of people, day after day; students, parents, strangers, navy cadets. Some really senior academics came to sling crates, though I could never quite bring myself to think that fitting work for them, neither in itself, nor, more rationally, a good use for the skills of people used to handling old documents.

I tried to send them to the conservation tent when I could. Some of them refused and kept on hauling crates.

In the end we’d moved enough stock to wrestle the empty compactus units off their rails and open up more alleyways and work them simultaneously, and so in the end it all got done.

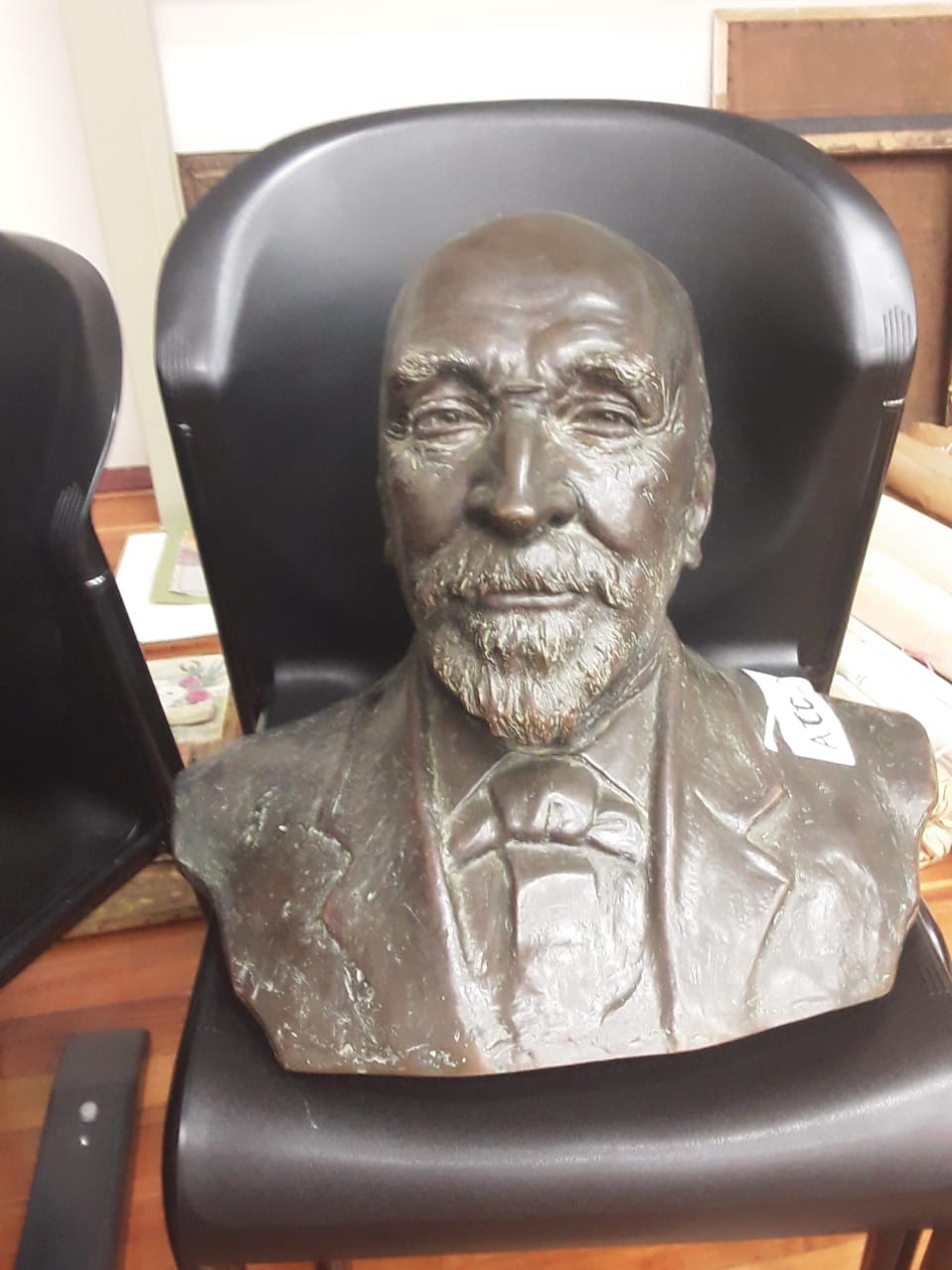

I personally found the bust of Mr Jagger and carried him out – the last of the statues to leave.

But that is not quite the end, because, after that, unharmed in the ashes,

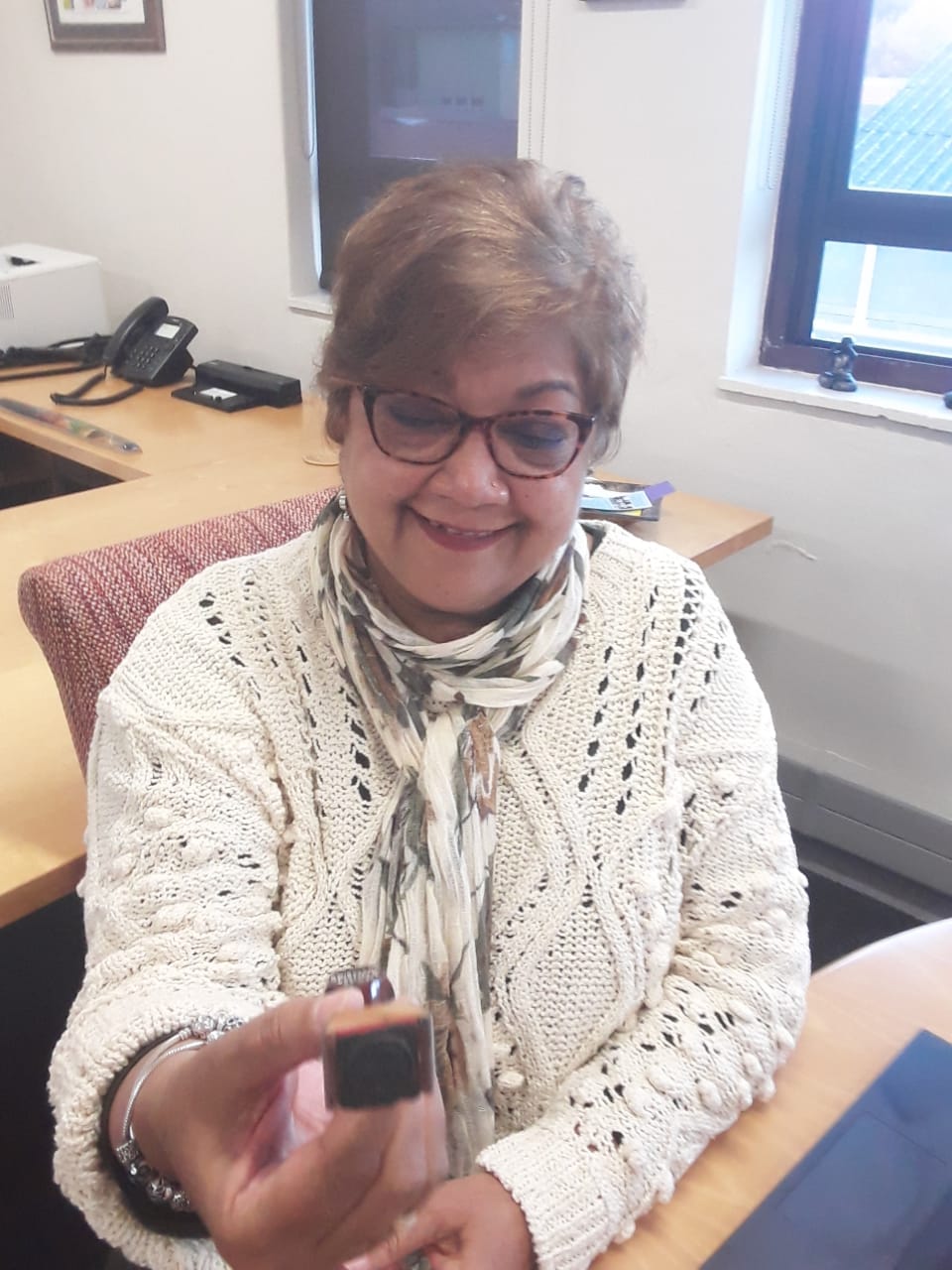

I found the old library stamp. It seemed only fitting that I should bear it up from the ruins with great ceremony and deliver it to the Executive Director!