By André Landman

As a long-time Joseph Heller fan, I have read most of what he has written. I have read all of his novels several times, always delighting in his dark humour and satirical style. But the novel I revisit most often is his anti-war cult classic, Catch-22.

Recently, Catch-22 visited me. Not the novel, or the film, but in the form of a photograph album. I know that sounds rather strange, so allow me to explain.

I recently processed a small collection known as the Julian Ozinsky Papers. Roughly half the papers had to do with Ozinsky’s involvement in Jewish cultural organisations. The other half had to do with his exploits in the Second World War. He served as an aerial photographer with the South African Air Force, first in North Africa, and then in Italy.

So what does this have to do with Catch-22?

Let me begin by removing the italics. Catch-22. The title of Heller’s novel has entered our lexicon, with a variety of meanings centred on the idea of a paradoxical or illogical situation. One such sense, according to Merriam-Webster, is “a situation presenting two equally undesirable alternatives”. It was in this sense that the Julian Ozinsky papers presented me with an “archival Catch-22”, in the form of a photograph album.

As I indicated before, half of the collection documents Ozinsky’s war experiences. The photograph album falls into this category. As I opened it, I experienced two conflicting emotions – wonder and dismay. Wonder because the photographs were a rich pictorial record of the aerial war and the role of 3 (SA) Wing in North Africa and Italy; dismay because the photographs had been stuck into the album with adhesive tape!

“Do not dismantle photograph albums and scrapbooks,” Mary Lynn Ritzenthaler writes. “They possess their greatest historical significance and artefactual value as whole original objects; the photographs should be seen in the sequence and context that was imposed by the creator” (Photographs: Archival Care and Management, 2008, p. 248). Indeed; but what about that adhesive tape, and the threat of damage to the emulsion onto which it was stuck?

With painstaking caution, I worked my way through the album, trying not to dislodge any photographs. It was apparent that the album itself did not date from the war years; it was actually more like a simple scrap-book than an album. It was also apparent that the photographs were not in any sequence. In fact, many had come loose over time and had been relegated to the back pages of the album, sans tape. In consultation with the donor, it was decided that the album was of no sentimental or historical value. That, and the fact that the photographs were not in any sequence that had meaning but had simply been pasted into the album in a haphazard manner, made it easier to resolve this Catch-22.

I decided to remove the photographs.

Working as carefully as possible, photograph by photograph, I loosened the adhesive from the black paper page of the album. To my relief, I found that the adhesive had become so dry that minimal pressure or force was needed to remove it, and the adhesive tape lifted off the print equally effortlessly. No damage was detectable. A very light clean with an appropriate cloth was applied to remove any traces of residual adhesive.

And so the photographs were removed, and the album discarded.

Which brings me back to Catch-22, italicised, i.e., the novel.

Processing the prints that I had retrieved from the album involved elements of traditional processing and digital processing. Apart from taking care to rehouse the physical objects in a manner that would ensure their longevity, I also wanted to digitize them, for access as well as preservation. As I worked through the prints, capturing metadata for the digital objects, cleaning and re-housing the originals, it struck me that many of the images could well have come directly from the pages of Heller’s Catch-22.

Heller, you might recall, was himself a bomber pilot in the Mediterranean theatre. He flew more than 60 missions. Ozinsky was attached to a bomber squadron, and the missions he flew would have been very much the same as those flown by Heller and described in Catch-22.

And so it was that as I arranged and described and metadata-ed and scanned and cleaned and re-housed and boxed and did all the other things an archivist does, I was lost in the parallel worlds of the real Ozinsky and the fictional Yossarian as they flew their missions over the war-torn landscapes of Italy and beyond.

Indulge me for just a while and I will try to illustrate what I mean.

Heller’s novel is set on the island of Pianosa. The men live in tents. Yossarian shares a tent with Orr, who was always trying to make the tent more liveable, much to Yossarian’s chagrin. Worse, “The dead man in Yossarian’s tent was a pest, and Yossarian didn’t like him, even though he had never seen him.” I doubt Ozinsky had the same problems, or tent mates, but these images reminded me of the many hilarious tent scenes in the novel.

Like Yossarian, Ozinsky was attached to a bomber wing. The planes they flew in may have been different, but the missions were much the same.

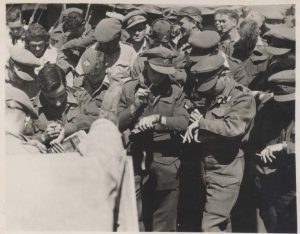

Milo Minderbinder was the powerful mess officer who created a “syndicate” (M&M Enterprises) in which everyone had a share. In this image (pay day in the real war), I imagine Milo trying to explain to Yossarian how he was able to buy eggs in Malta for seven cents apiece and sell them at a profit in Pianosa for five cents.

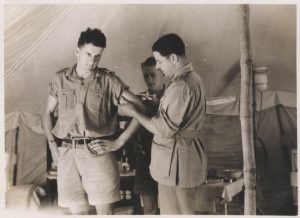

One of my favourite supporting characters in the novel is Doc Daneeka, the squadron’s physician. But Doc Daneeka leaves the doctoring to his two orderlies, Wes and Gus, while he indulges his hypochondria and does all he can to avoid dying. In this image, I imagine Wes and Gus giving Doc Daneeka an injection …

In Catch-22, Yossarian and his friends often frolic on the beach. It seems from images such as this that Ozinsky and friends did the same.

A key moment in the novel is the death of Snowden. He was manning a gun turret much like the one below when he was shot. He died in Yossarian’s arms. “Where are the Snowdens of yesteryear?” is another Catch-22 phrase that has entered the popular culture.

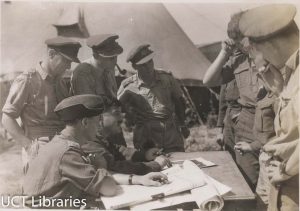

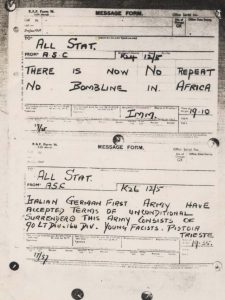

At one point, Yossarian is terrified because his squadron has been “volunteered” to bomb Bologna, which they know will be heavily defended. In a desperate bid to save his own life, he sneaks into the ops room and moves the bomb line past Bologna. As I looked at the first of the two photographs below, I could just imagine the perplexed officers saying, “Look! The bomb line is past Bologna! The city has been captured. We don’t have to bomb it after all.” The other image shows an official notice that the bombing in North Africa was over, since the German and Italian armies had surrendered. What Yossarian wouldn’t have given to see one of those with Italy on it in place of Africa.

“’Now, men, we are going to synchronise our watches,’ Colonel Korn began …”

I could go on and on, but I think you can see why a Joseph Heller fan like me would draw the obvious similarities between Yossarian’s fictional experiences as portrayed on the printed page and the real-life experiences of Julian Ozinsky as captured by these photographs.

My aim with this post is twofold.

The first aim is to draw attention to an on-going (and potentially never-ending) project to arrange and describe all photographs housed in legacy collections in an overarching “photograph collection”. Many of the collections taken in at UCT Libraries Special Collections over the decades have significant photographic components. These photographs have untapped documentary, historical, and social value. Unfortunately, in most cases they are either not described at all, or described in a rudimentary fashion, thus limiting accessibility. Many are also in danger of degradation, making physical and digital preservation a necessity.

The second aim is to shine a spotlight on the photographs in the Julian Ozinsky collection. Once they have all been digitized, they will represent a significant record of the South African Air Force’s role in the war, and should be of interest to military and aviation historians.

They will also be of interest to historians of Jewish South Africans. An as yet unresolved issue relating to Catch-22 concerns Yossarian’s nationality. Many have speculated that he was Jewish. Based on this album, I’ say he was.

The Julian Ozinsky Papers are described here.

A sample of the photographs from the album can be viewed here.

In time, they will all be accessible online. And there won’t be a catch, not even Catch-22 …