by Busisiwe Khangala & Sandra Rowoldt Shell (retired), African Studies Library, Special Collections, University of Cape Town (UCT)

This post is adapted from a paper originally presented in 2009 at Emory University for the ‘Images Of Power’ poster exhibition, including posters from the collections of the African Studies Library at UCT and Emory University Libraries

The Ephemeral Nature of Posters

Posters form an important part of contemporary public visual communication, aiming, in the most part, to sell or propagate a product or an ideology – to transmit ideas, values and messages. They are ephemeral by nature – visual representations made for very specific purposes within a time and place.

The effectiveness of the poster as a political tool throughout the twentieth century, and in particular, the South African anti-Apartheid Struggle, lies in its immediacy, and its ability to reach the broad mass of ordinary people. Before the advent of social media, the poster served as a vital tool of mass communication, readily accepted and understood by the public at large.

…………………………………………………………………….

History of the Poster

The remnants of ancient culture found in African rock art, Egyptian hieroglyphs and ancient Pompeii served a similar function to the modern poster: publicly communicating through symbols and imagery. The very first posters as we know them were hand-drawn on paper and were used largely for official proclamations.

Perhaps the first revolutionary poster was the single sheet of paper fixed to the door of Castle Church in Wittenberg by Martin Luther on the 31st of October in 1517. It contained his 95 theses or points of dissent from the teachings of the Roman Catholic Church. (Image source: Fellowship Presbyterian Church)

While Luther’s poster was hand-produced, the introduction of movable type and the invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg in the 1440s had already facilitated the mass production of bills and posters.

Printing technology made it possible not only for the official proclamations of ruling and conquering powers but also for dissenting movements to harness this idiom for posting their own political messages on the streets and thereby to mobilize support for their cause. (2)

Mass-produced pictorial posters came into their own during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, as the specters of war and revolution gripped the world. (3) Posters were used widely during the two World Wars, by Allied and Axis powers alike.

The iconography of revolutionary Russia is particularly memorable for its bold, often stark, imagery.

(Source: Soviet Propaganda Posters of WWII)

The London Opinion poster of Lord Kitchener’s mustachioed face during the First World War, his pointed finger and his exhortation “Your country needs YOU” was emblazoned on public walls throughout wartime Britain, c. 1914

(Source: Wikipedia)

Nazi Germany used propaganda posters to espouse its anti-Jewish propaganda and to promote its racist Aryan ideology. The post-war International Military Tribunal recognized the impact of propaganda to incite genocide, and demagogues such as Nazi zealot Julius Streicher were indicted on counts of crimes against humanity. (Source: Schragenheim Collection, SAHGF Archives, UCT Special Collections)

Revolutionary forces in Franco’s Spain spawned a powerful and vigorous genre of poster imagery, creating some of the finest posters the world had yet seen.[4]

……………………………………………………………………..

……………………………………………………………………..

The Poster in the South African Anti-Apartheid Struggle

Following the 1960 banning of political movements and the imprisonment of their leadership, parliament, the stage, the courtroom and the pulpit were eventually the only arenas where the public transmission of anti-apartheid sentiment could be expressed with any modicum of impunity. The published word was censored and ‘undesirable’ texts were banned.

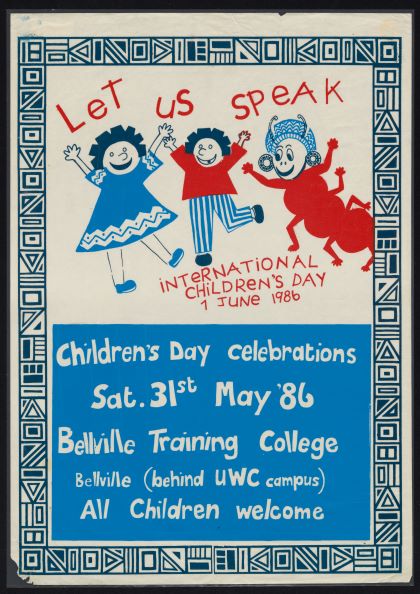

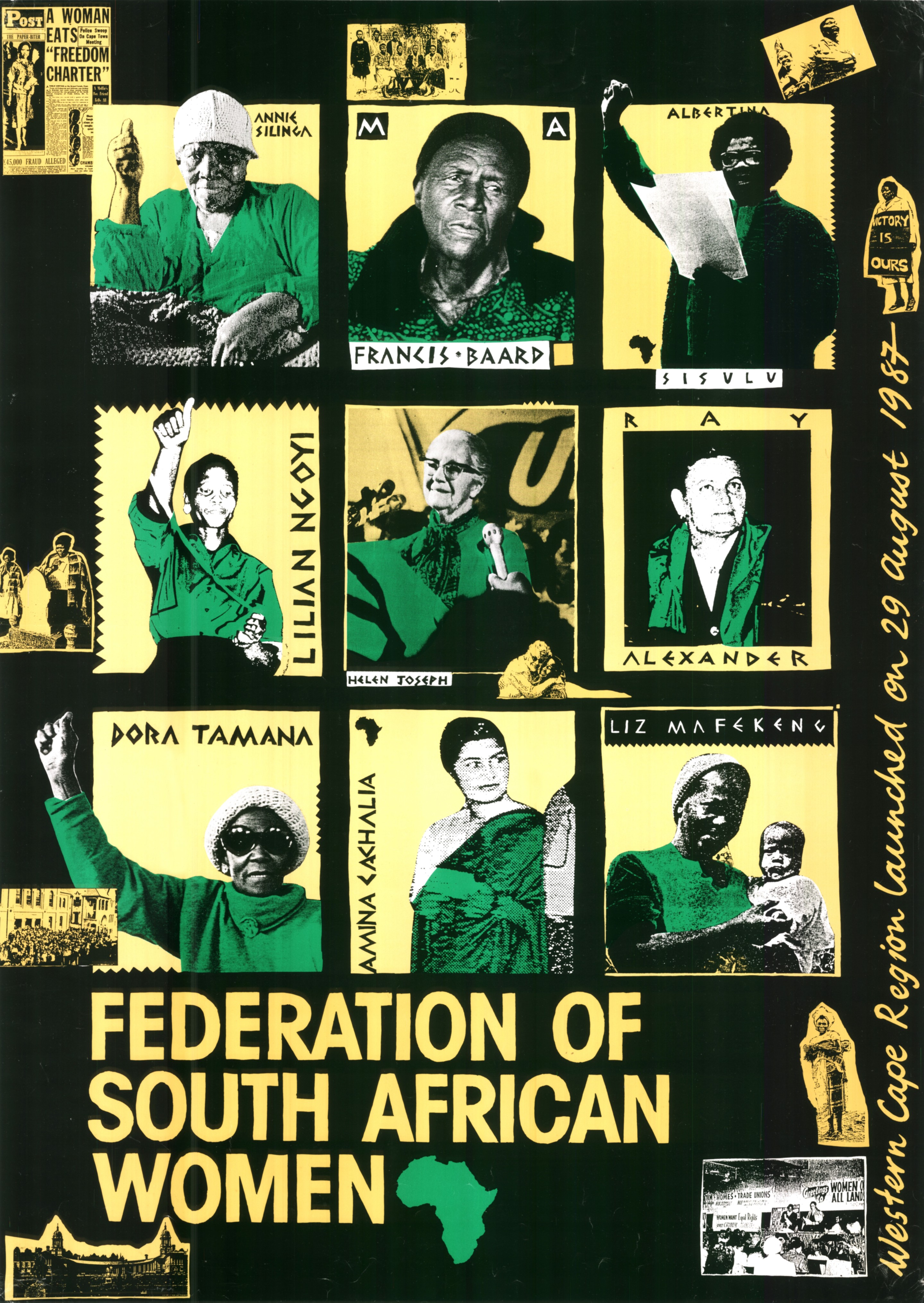

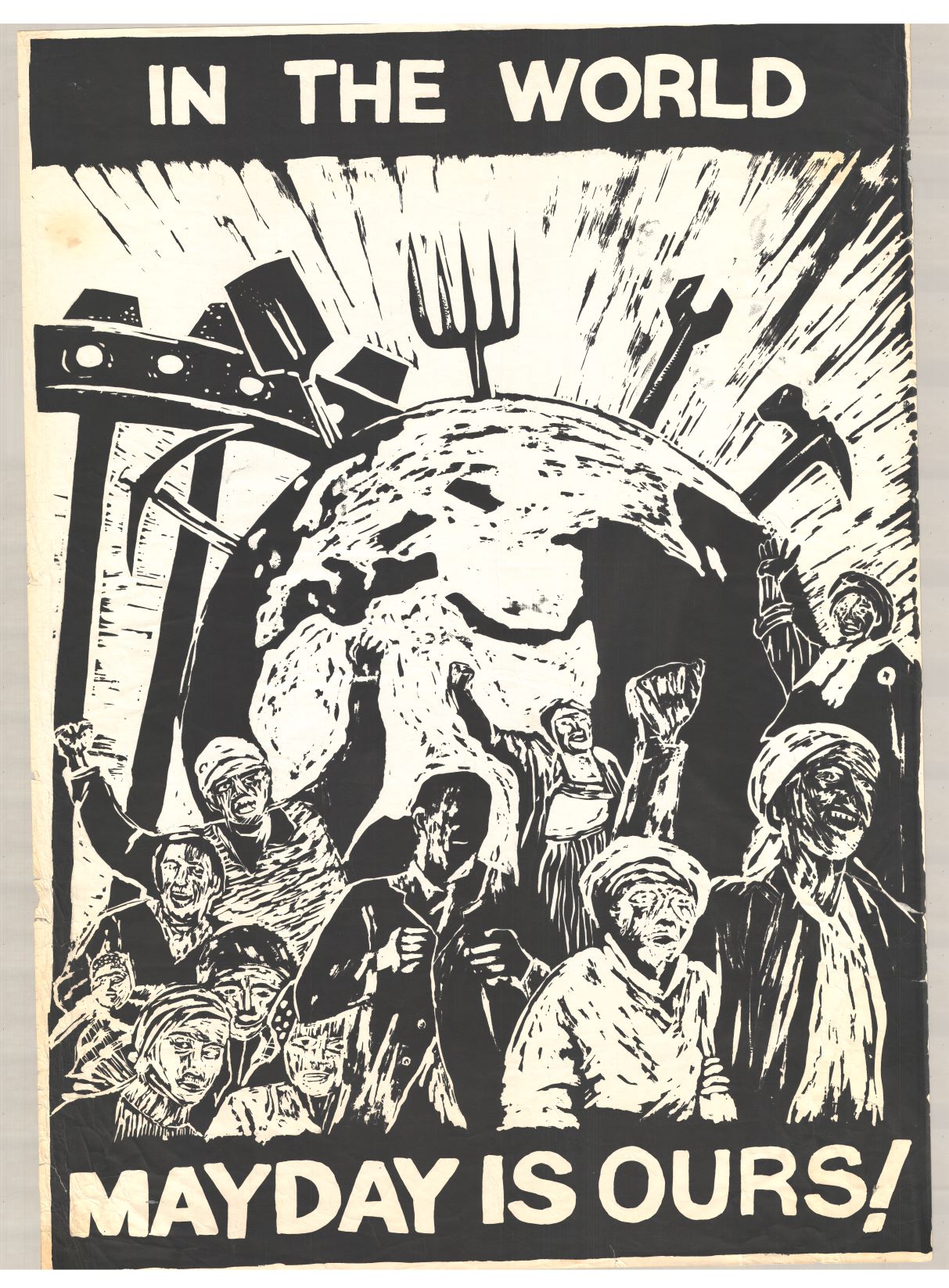

South Africa’s struggle poster emerged as a form of revolutionary idiom in the late 1970s. This coincided with the emergence of a mass movement of loosely affiliated grassroots based organisations and civil organisations from across all walks of life who fueled the reemergence of a powerful anti-apartheid struggle. Communication relied heavily on symbols in song, dance and graphics. Posters, t-shirts, lapel buttons and even bumper stickers carried the messages of resistance and revolution. Symbols, slogans and images became the shorthand of the struggle at a time when communicating messages that ran counter to the apartheid regime’s doctrine and lexicon became increasingly difficult and dangerous.

…………………………………………………………………….

View the Primo record for this poster.

……………………………………………………………………..

……………………………………………………………………..

South African Struggle Posters as Images of Power

…………………………………………………………………….

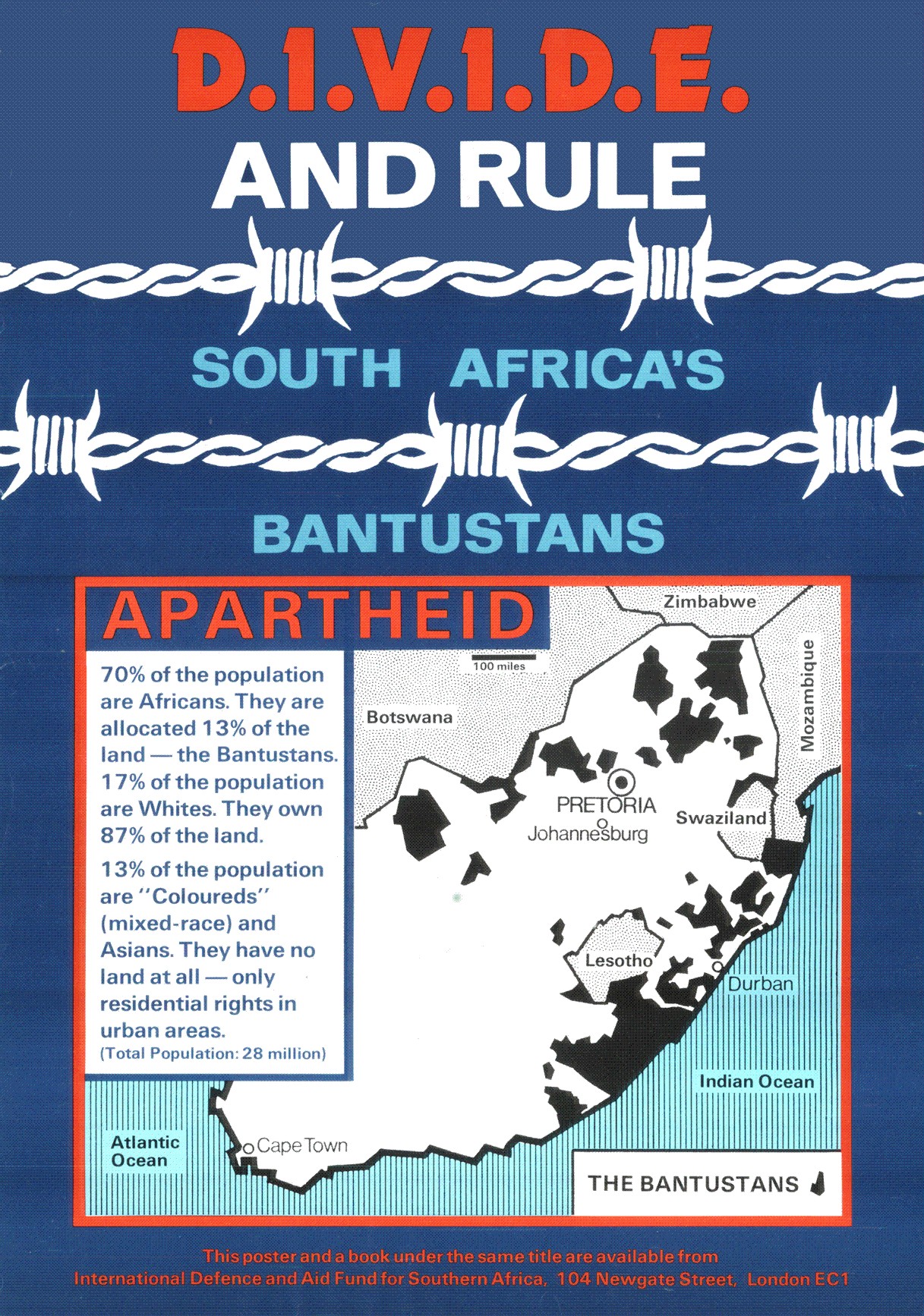

Power manifested itself in many ways throughout the struggle years and at times the might of the apartheid state seemed immutable. Apartheid—literally “the state of being apart” or “separateness”—lay at the core of the South African regime’s national strategy.

The white minority government recognised the latent power of the huge black majority and, by strategic administrative social engineering, undertook to dis-aggregate this majority into smaller, ethnically labelled pockets separated from one another geographically and scattered across the country.

One of the most iniquitous moves of the apartheid regime was its policy of enforcing separate areas for different racial groupings, a system which lay at the very core of apartheid. Under this system, the South African government created a series of “Bantustans” (ethnic homelands) where it intended all black South Africans, comprising 70% of the total population, to live. These Bantustans comprised 13% of the total land area of South Africa. This left 87% of the land for the use of the population classified as ‘White’, comprising a mere 13% of the total population.

The Coloured and Asian members of the population were allocated no land at all beyond limited residential rights in urban areas. Black farmers who had farmed land for generations lost their ownership rights and, between 1960 and the early 1980s, an estimated 3.5 million people were removed from their homes, many being relocated in the “Bantustans” or so-called “homelands”.

……………………………………………………………………..

View the Primo record for this poster.

……………………………………………………………………..

…………………………………………………………………….

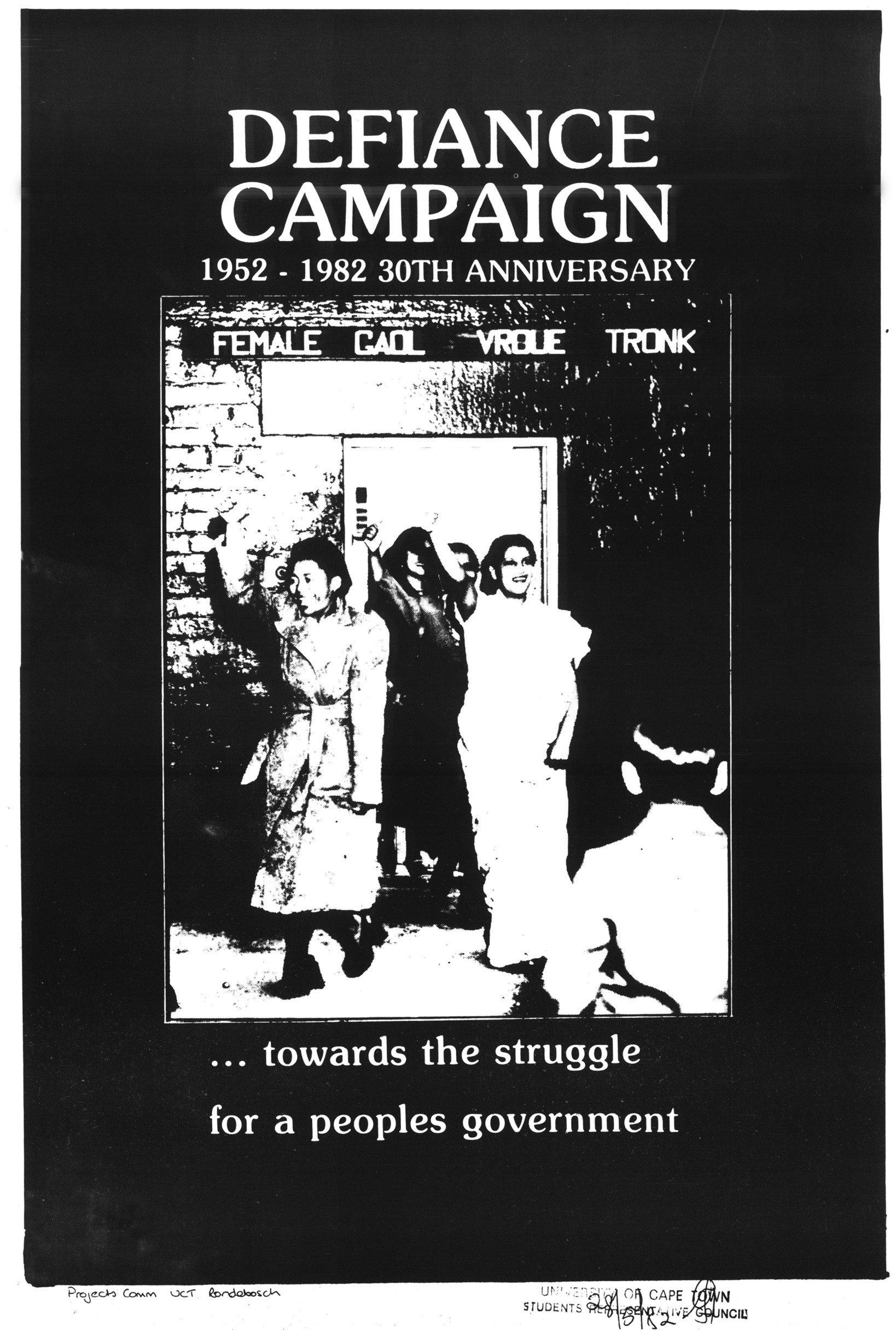

Despite the dominance of the South African apartheid regime, strong resistance emerged soon after the National Party victory at the polls in 1948. The early 1950s saw a new commitment to resistance and civil disobedience. On 26 June 1952, the African National Congress, together with the South African Indian Congress (SAIC), launched the Defiance Campaign against Unjust Laws. The Campaign constituted the largest movement of non-violent resistance in South African history and it was the first to be supported by members of all racial groups under the leadership of the ANC and the SAIC.

…………………………………………………………………….

View the Primo record for this poster.

…………………………………………………………………….

View the Primo record for this poster.

…………………………………………………………………….

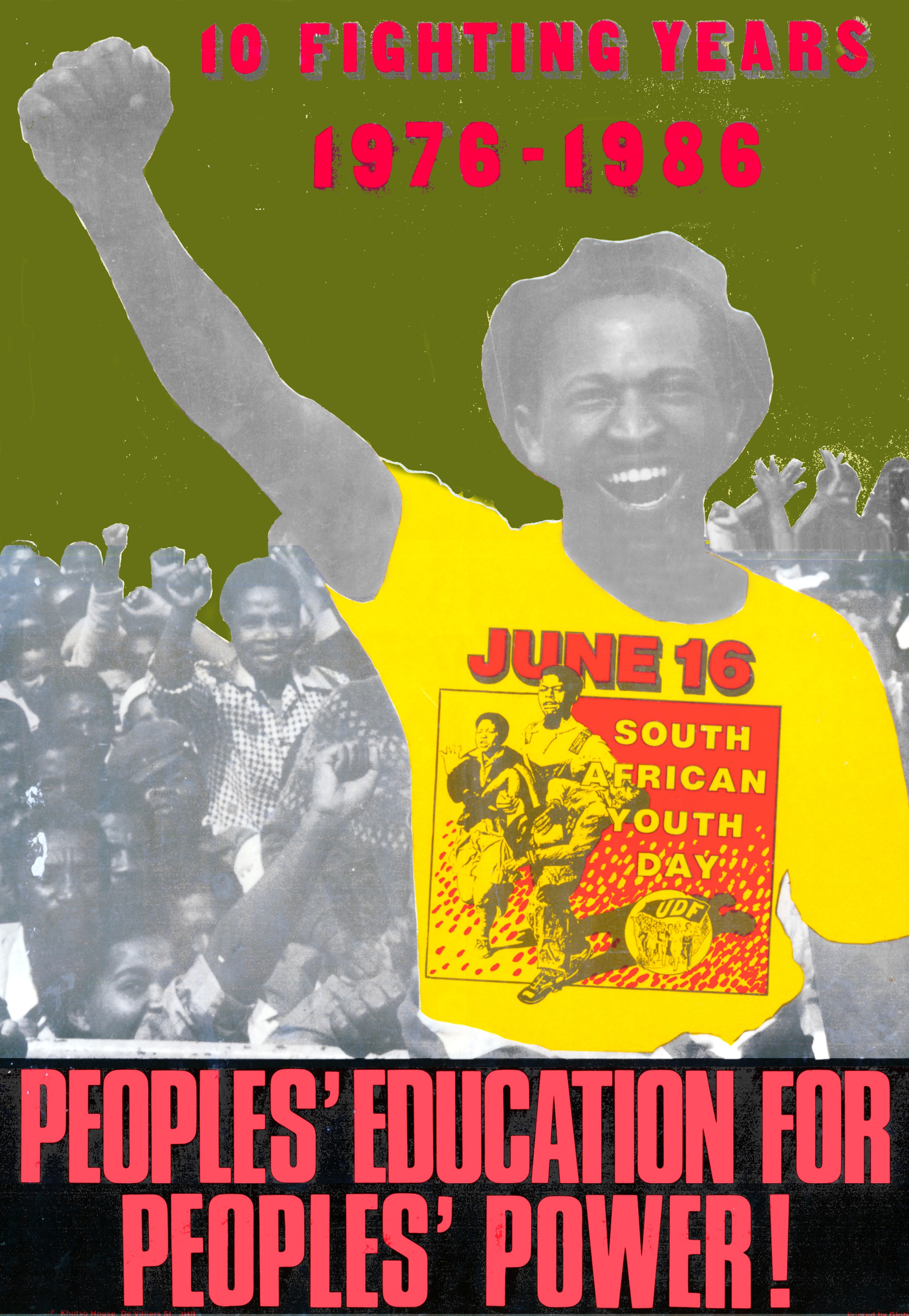

On 16 June 1976, the students of Soweto sparked a nationwide protest against the iniquities of “Bantu” education and the apartheid regime.

(Pictured) An insert of a poster series by the Community Arts Project, circa 1991, featuring Nzima’s iconic photo.

(Image source: African Studies Library, Special Collections, UCT Libraries.

View the Primo record for this poster.

View the finding aid for the Community Arts Project Archive in Special Collections

…………………………………………………………………….

This poster, commemorating the tenth anniversary of the Soweto uprising, pays tribute to the bravery of these children.

View the Primo record for this poster.

…………………………………………………………………….

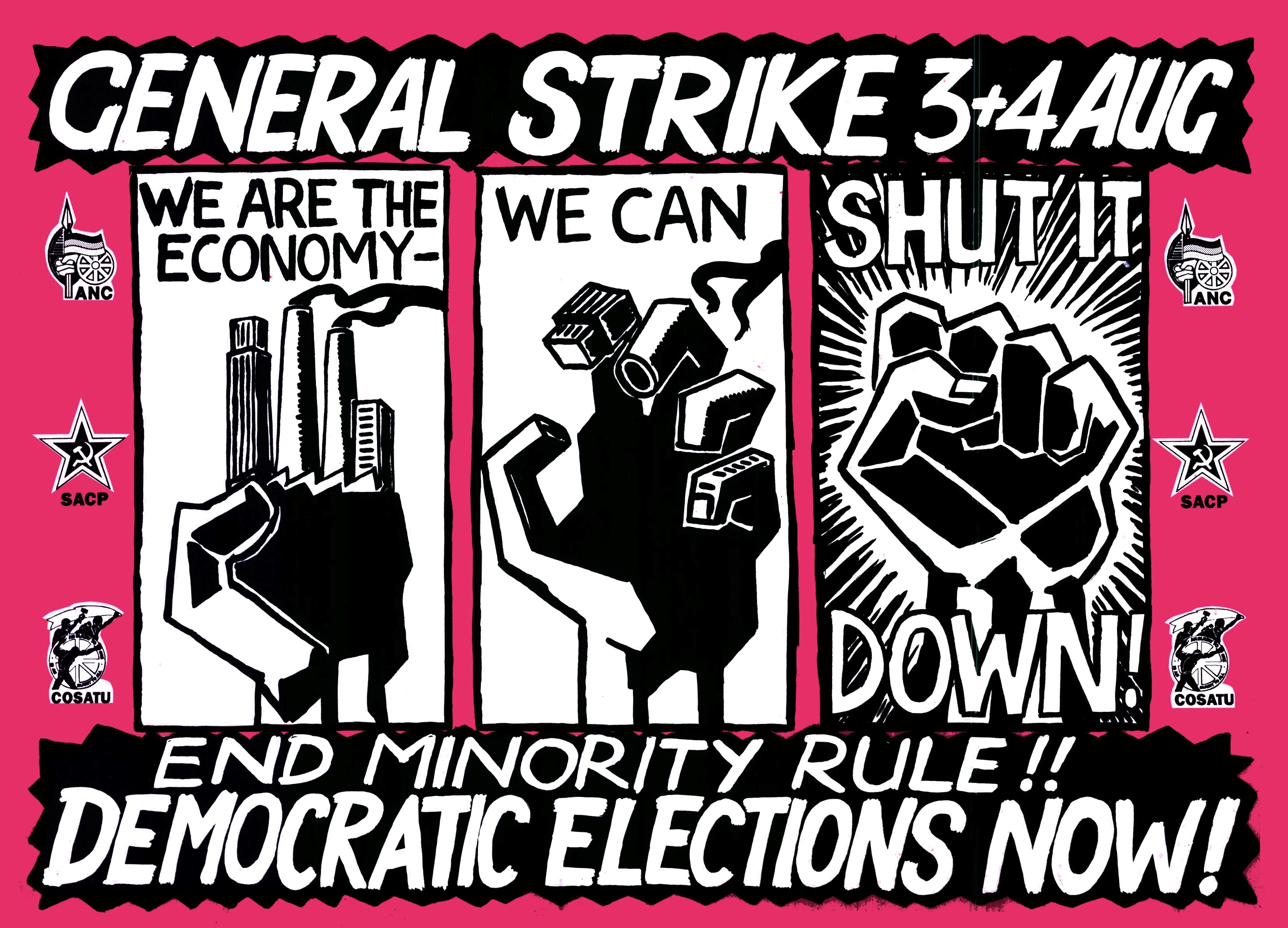

The apartheid government systematically exploited the black South African labour force, but the broad based radicalisation and organisation of workers in response resulted in a powerful form of opposition.

View the Primo record for this poster.

View the Primo record for this poster.

…………………………………………………………………….

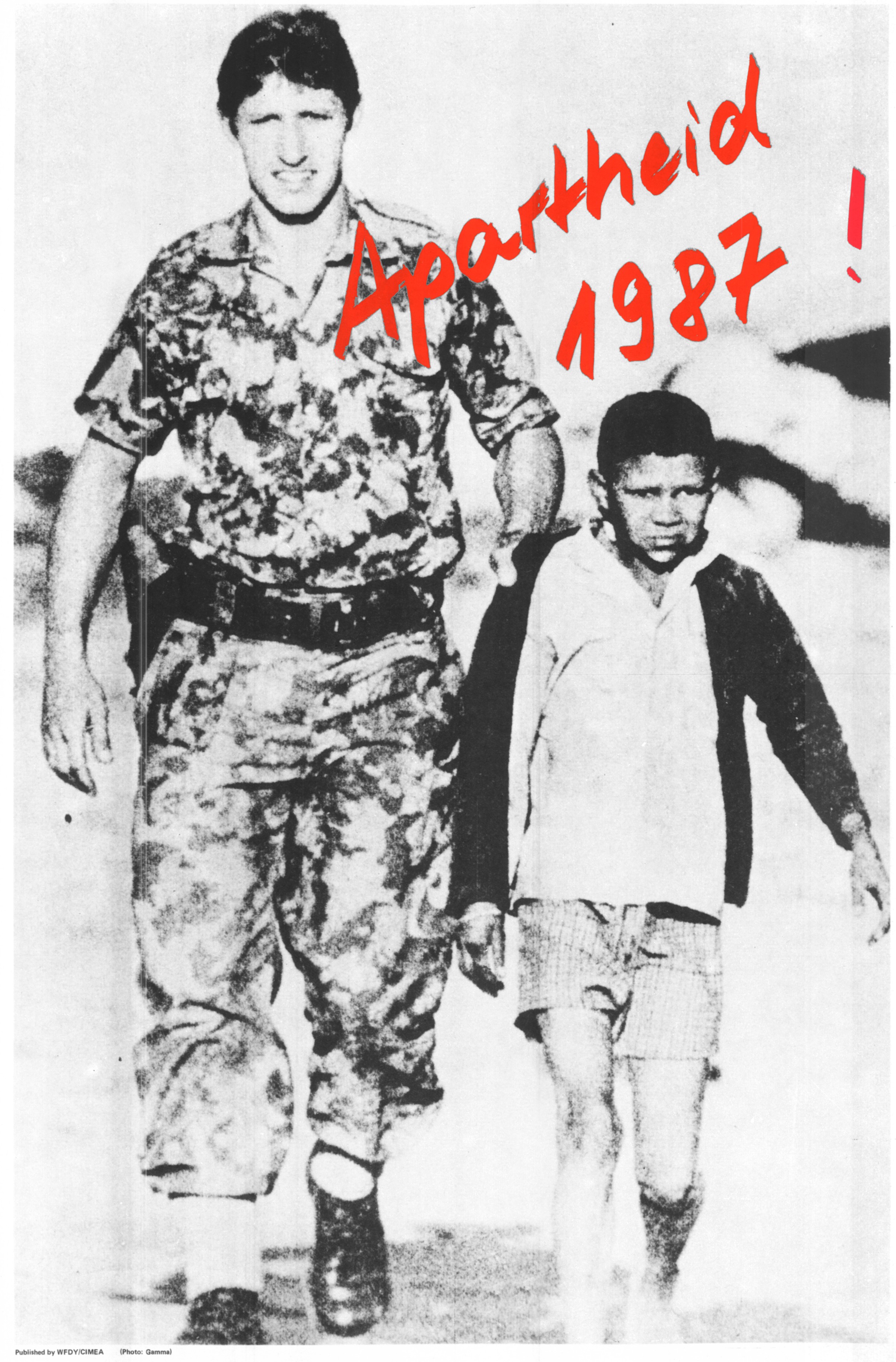

During this period, the South African armed forces exerted considerable power and, through a system of compulsory military service for all young white male school-leavers, was a self-perpetuating, renewable resource of force.

View the Primo record for this poster.

…………………………………………………………………….

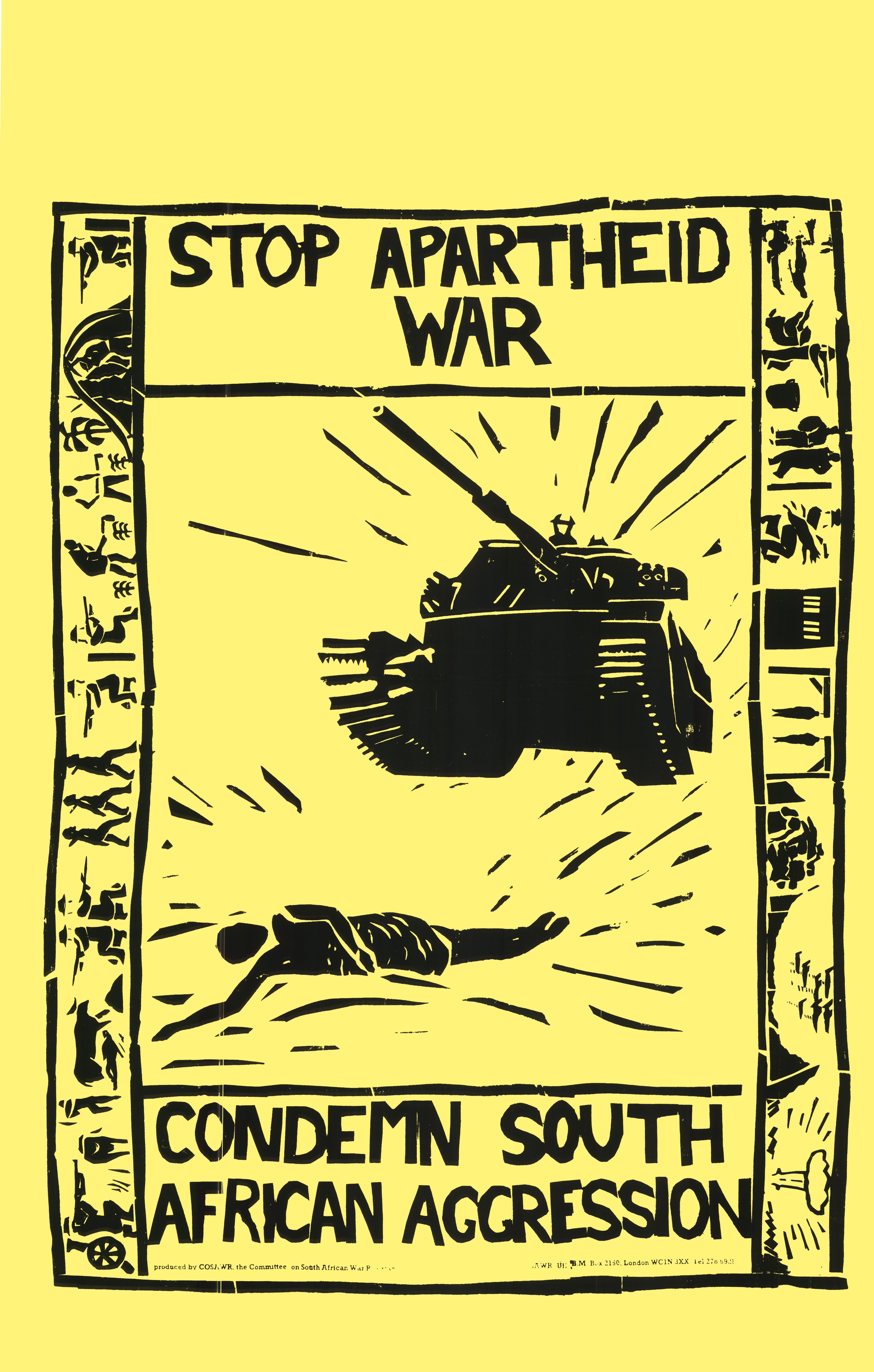

The Committee on South African War Resistance (COSAWR), the End Conscription Campaign (ECC) and other anti-militarist groups were instrumental in focusing international attention on the increasing militarization of South Africa. Internally, they provided a forum for dissent and a support system for a growing number of conscientious objectors. These pacifist movements served as a mechanism for white South African men to oppose the Apartheid regime by refusing to serve in its military.

View the SAHA record for this poster.

COSAWR was founded in 1978 with the merging of two groups of South African war resisters then active in Britain. It was intended as a self-help organisation for South African military refugees and as a means of raising the issue of militarism in South Africa. Its members also conducted considerable research into the South African military structure and resistance. It published a journal under the title Resister which became the leading magazine on South Africa’s militarization. At the end of 1990, the Committee deposited its archives in the Manuscripts and Archives Department of the University of Cape Town Libraries.

View the finding aid for the COSAWR Collection in Special Collections.

View the Primo record for this poster.

…………………………………………………………………….

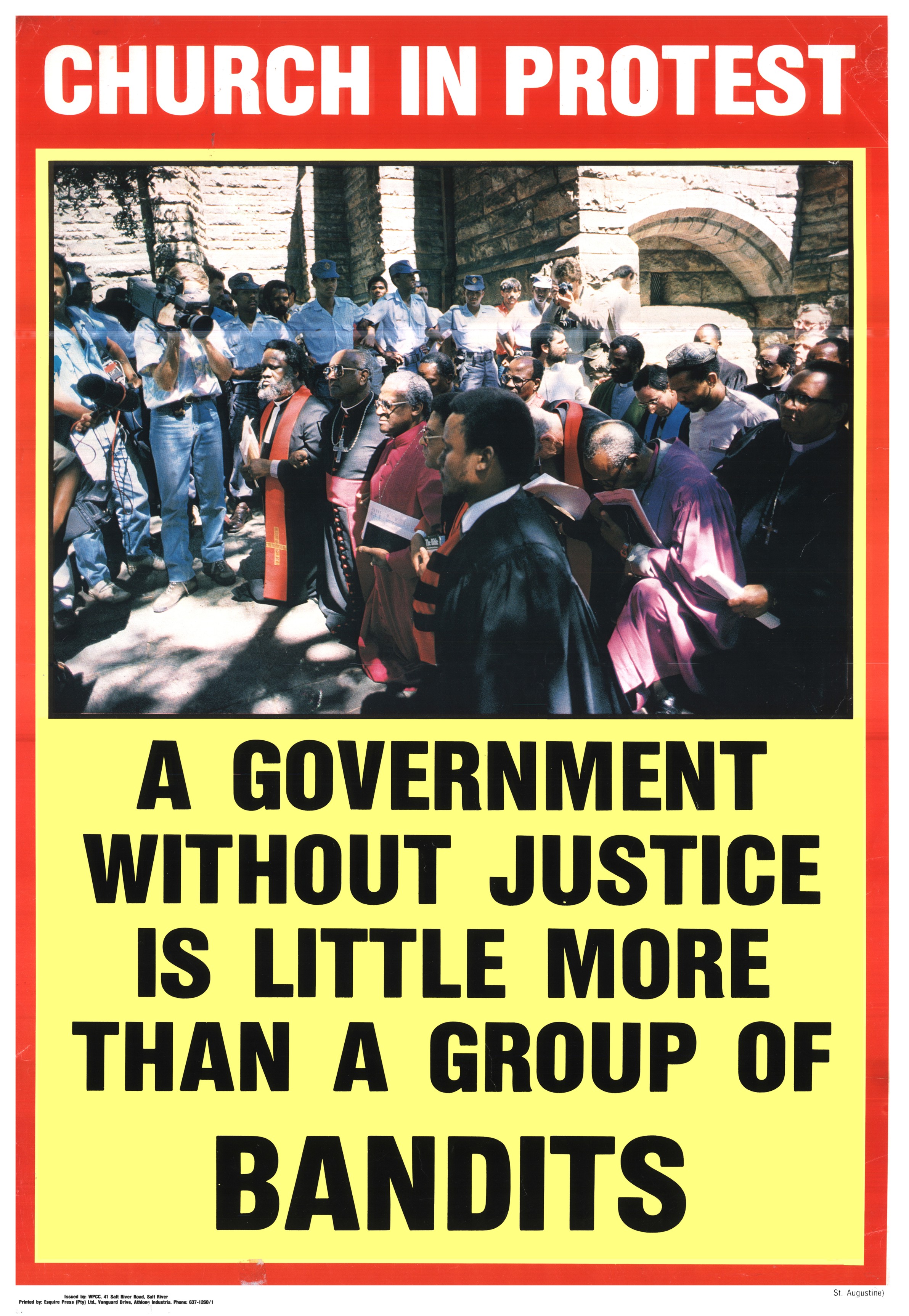

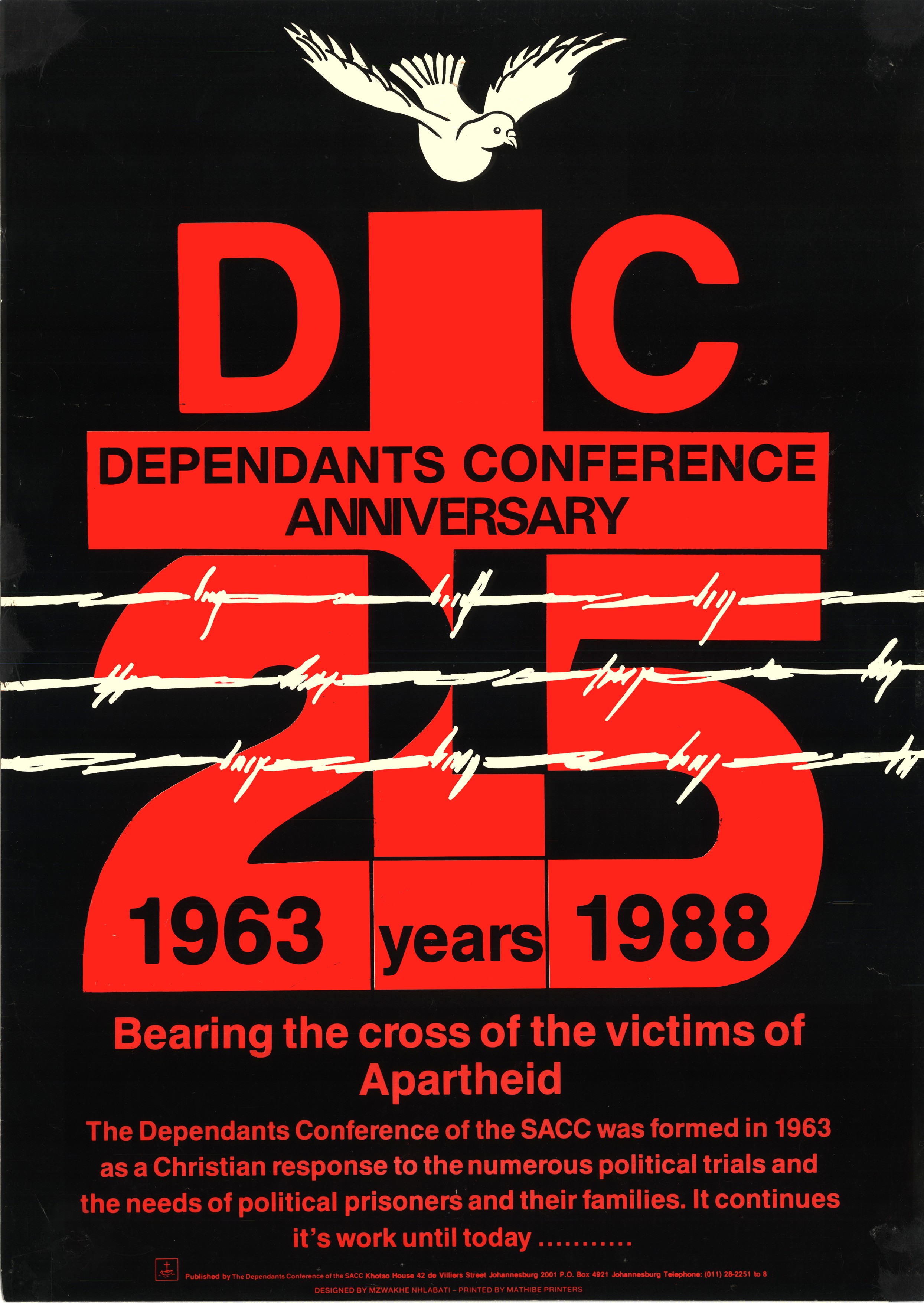

Church and other faith groupings played a significant role during the struggle years. Not only did they provide a forum for protest, they also offered both spiritual and material support for those victimised by the apartheid system. Groups such as the South African Council of Churches, the South African Muslim Council and the Dependants’ Conference played a vital supportive role.

With a growing number of activists jailed or detained without trial by 1963, the South African Council of Churches formed the ecumenical Dependants’ Conference (DC) to care for the families of those behind apartheid bars. This initiative not only gave support to the families, it provided legal aid, facilitated family visits and developed programmes to assist detainees with their study needs. DC formed a major aspect of the SACC’s activities throughout the struggle years.

Archbishop Tutu had been called to the Cathedral where he successfully negotiated with the police surrounding the building to allow the protesters to disperse peacefully. Leaders such as Archbishop Desmond Tutu led, counselled and comforted the people during these stark and dangerous years.

View the Primo record for this poster.

…………………………………………………………………………………….

This poster, issued in 1988, marked the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Dependants’ Conference. It also illuminated the powerful persistence and determination of countless volunteers in offering comfort, help and hope to those incarcerated by the apartheid state and their families.

Insert: “The Dependents Conference of the SACC was formed in 1963 as a Christian response to the numerous political trials and the needs of political prisoners and their families.”

View the Primo record for this poster.

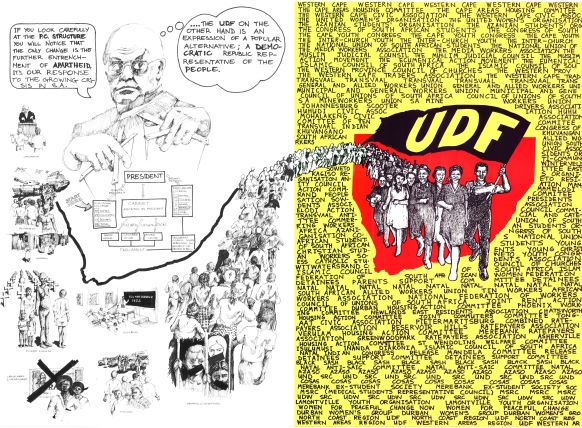

The power of the people grew steadily through the 1970s and early 1980s culminating in the formation of the United Democratic Front (UDF) in August 1983. The UDF brought together a wide range of grassroots anti-apartheid groupings under one loose banner, allowing for a massive aggregation of people’s power under one resolute umbrella. According to Judy Seidman in her work on the South African poster movement, the UDF logo was designed at a workshop held at Crown Mines and drawn by Carl Becker and Faizel Mamdoo. [5]

View the Primo record for this poster.

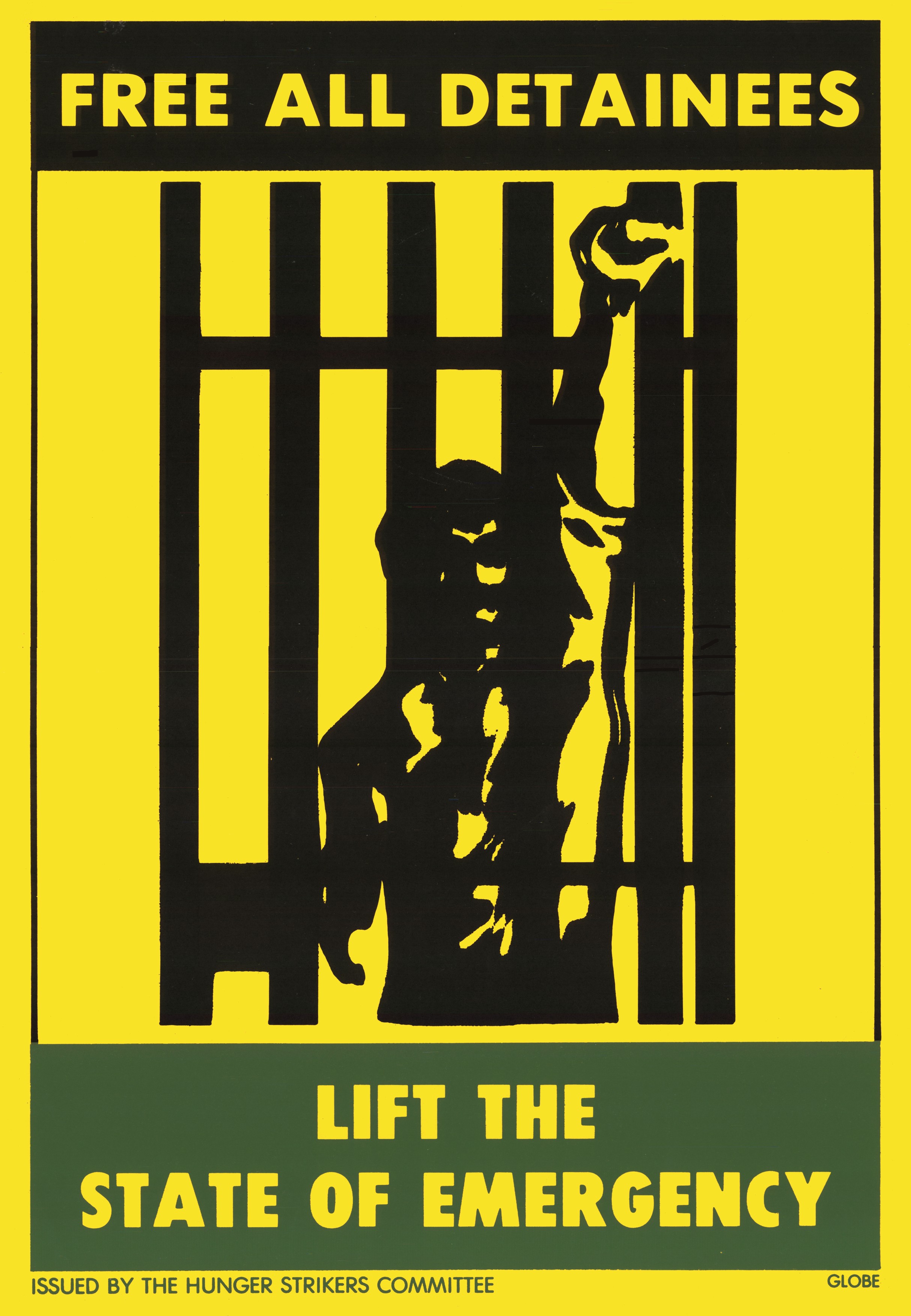

The mass movement provided momentum for intensive repudiation of state oppression, particularly during the 1980s when a State of Emergency was imposed in consecutive years. Calls were made to release political prisoners, especially following the controversial ‘death in detention’ of activists including Steve Biko, Ahmed Timol and Neil Aggett.

…………………………………………………………………………………….

View the Primo record for this poster.

…………………………………………………………………………………….

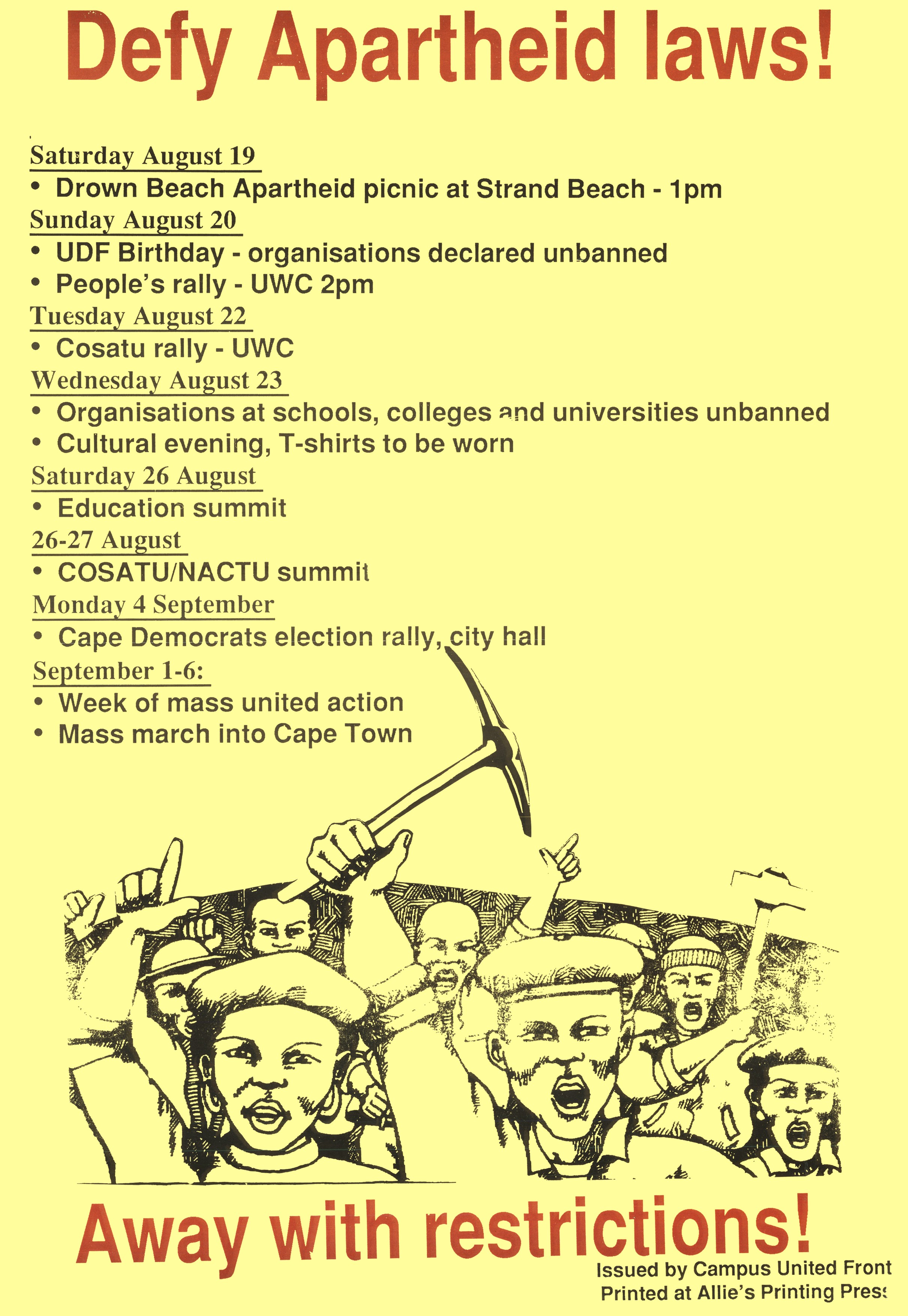

The struggle reached its climax in 1989 with heightened resistance and an escalation of protest measures previously employed during the Defiance Campaign – the aim was to make society ungovernable. Anti-apartheid organisations which had been restricted under State of Emergency regulations in February 1988 declared themselves “unbanned” and set up meetings. Hundreds of black people congregated on two segregated beaches outside Cape Town. Police response was quick and violent resulting in multiple arrests and beatings.

…………………………………………………………………………………….

View the Primo record for this poster.

……………………………………………………………………….

……………………………………………………………………….

South African Posters as a Tool for Democracy

……………………………………………………………………….

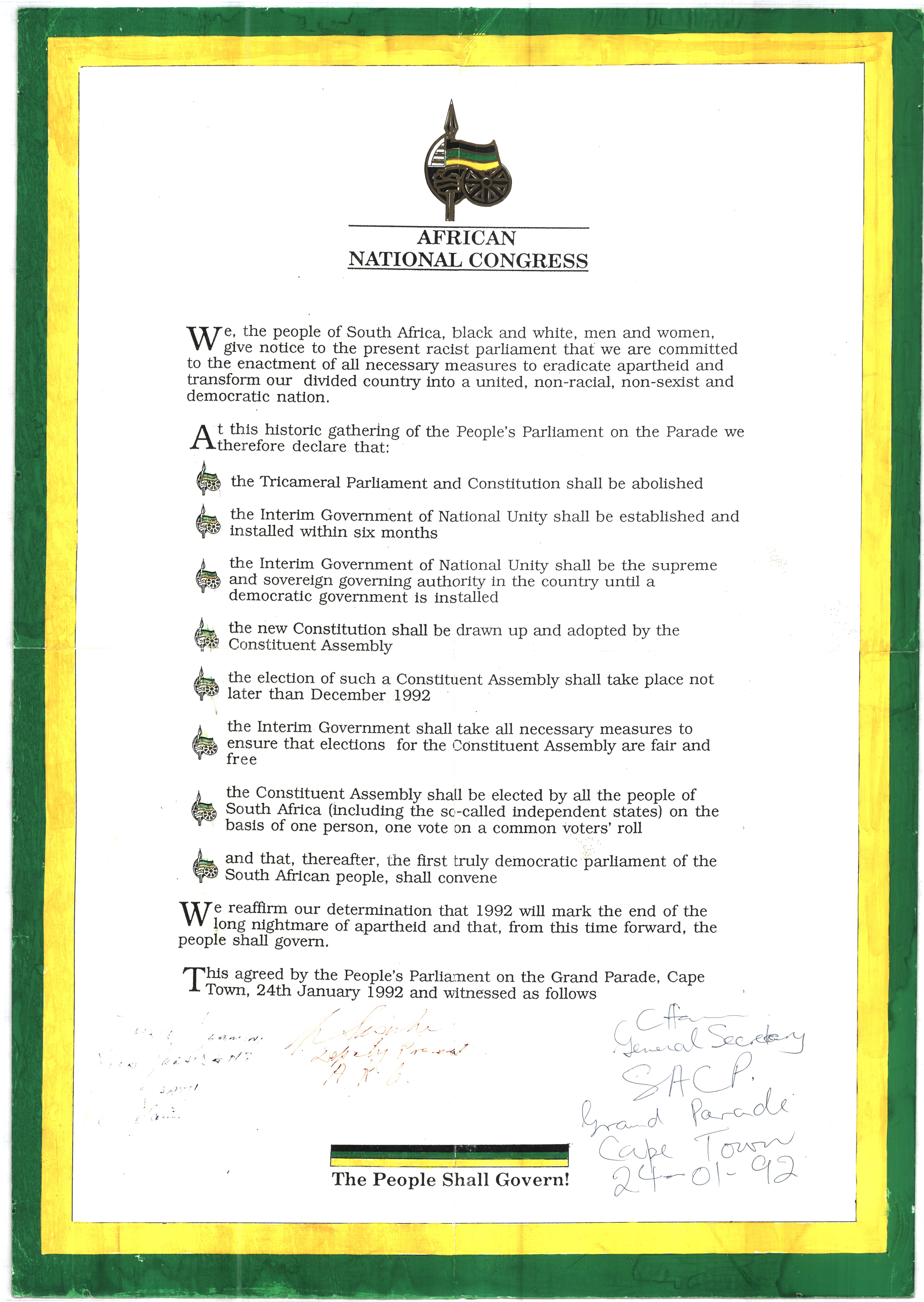

Until April 1994, the right to vote was reserved only for people classified as white according to apartheid rule. Disenfranchisement meant that the political will of the majority of the population was not accorded any significance. Early on in the struggle, the slogan “One man one vote” rang out with gathering and emphatic urgency.

……………………………………………………………………….

……………………………………………………………………….

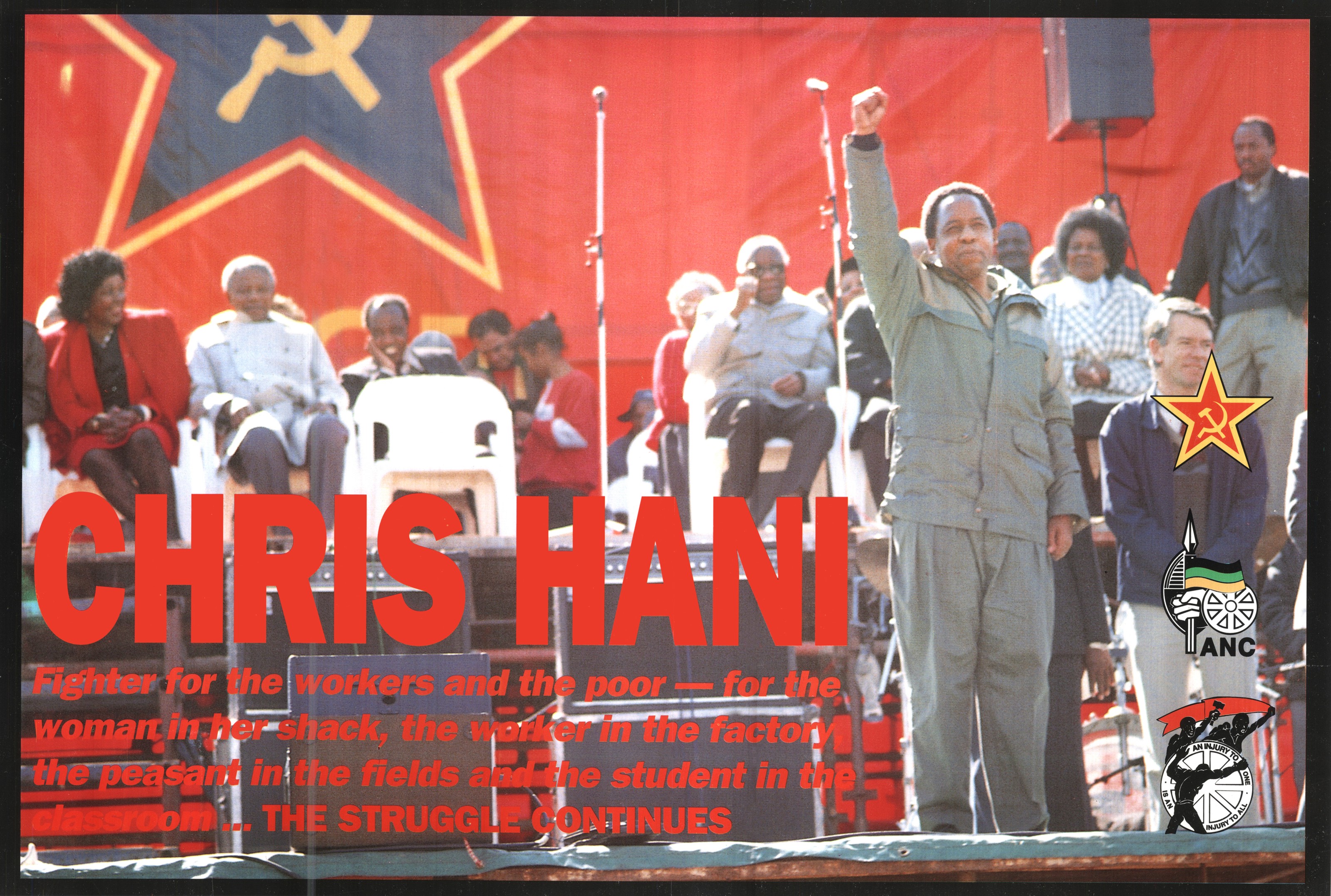

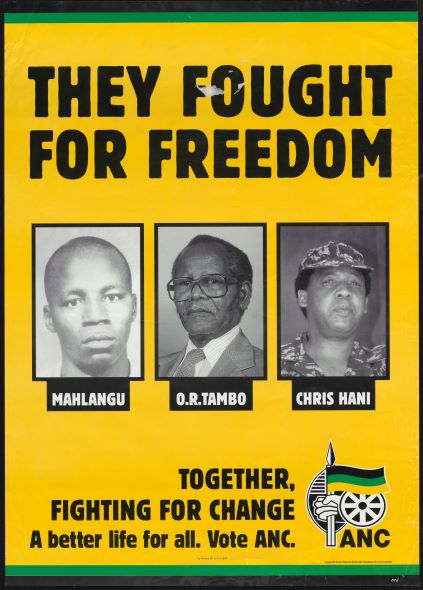

Significantly, one of the signatures featured on this poster is that of Chris Hani, then Secretary General of the South African Communist Party.

……………………………………………………………………….

This would be one of the last public documents he would sign as he was brutally assassinated little more than a year later on Easter Saturday, 10 April 1993. On that day, South Africa lost a great leader, one whom many believed would one day lead the country.

……………………………………………………………………….

View the Primo record for this poster.

View the Primo record for this poster.

……………………………………………………………………….

Hani’s murder took place on the eve of South Africa’s first free and democratic elections.

View the Primo record for this poster.

……………………………………………………………………….

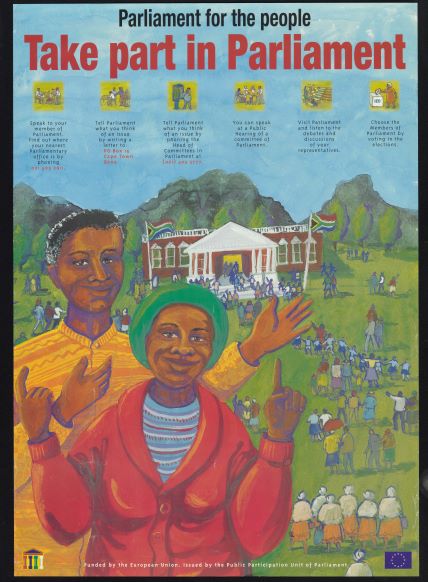

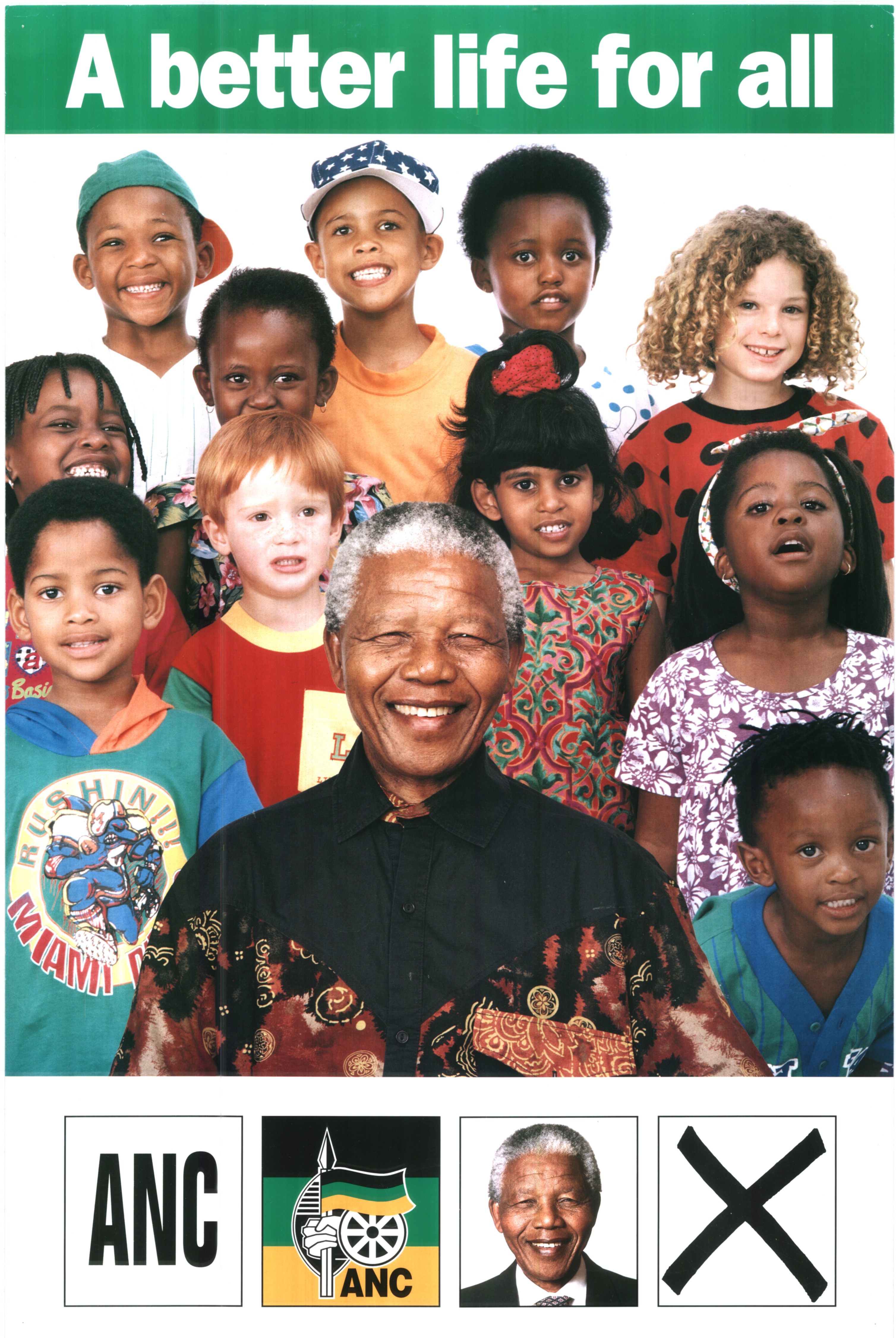

People flocked to the polls to cast that long-awaited vote for their own democratically elected government. In the lead up to the election, newly unbanned political parties used the poster idiom to urge all citizens to vote and to instruct citizens on how to do so, for the very first time. This momentous day is memorialised in numerous posters calling on the people to vote and describing the actual voting process.

……………………………………………………………………….

View the Primo record for this poster.

View the Primo record for this poster.

…………………………………………………………………………………….

For all the power of the people in the various groupings and organisations featured here, there was a need for strong leadership for them to be truly effective. South Africa has been blessed with notable leaders throughout the struggle and in these early years of our young democracy. First among these, of course, ranks Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela, known and honoured throughout the world for his wise and gracious leadership. The wisdom, courage and charisma which inspired and encouraged South Africans throughout his many years of imprisonment also united all South Africans as never before when, in 1994, he assumed the Presidency of the new and democratic South Africa.[6][7]

As first President of the newly liberated South Africa in 1994, Nelson Mandela quickly made his concern for the future of South Africa’s children one of his priorities. During his 27 years of imprisonment he, like other political detainees, was separated from his own children and from any active role in their development. On his release he became acutely aware that apartheid had robbed many of the country’s children of their basic rights to a secure home, education, training, health care and even to basic nourishment. To address these issues, he established the Nelson Mandela Children’s Fund as a means of providing “a better life for all” for South Africa’s children.

…………………………………………………………………………………….

View the Primo record for this poster.

The posters speak for themselves as they tell—graphically—the story of South Africa’s struggle for democracy.

List of sources

Barnicoat, John. Posters: a concise history. London: Thames & Hudson, 1972 (reprinted 1997).

Bonnell, Victoria E. Iconography of power: Soviet political posters under Lenin and Stalin. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997.

Gallo, Max. The poster in history; with essays by Carlo Arturo Quintavalle & Charles Flowers. New York: W.W. Norton, 2001.

Gouwenius, Peder. Power to the people! South Africa in struggle: a pictorial history. London : Zed Press Totowa, N.J : U.S. Distributor, Biblio Distribution Center, 1981.

Rickards, Maurice. The rise and fall of the poster. Newton Abbot: David & Charles London, [1971].

Rickards, Maurice. Posters of protest and revolution; selected and reviewed by Maurice Rickards. Bath, Somerset: Adams & Dart, 1970.

Rickards, Maurice. Posters of the First World War; selected and reviewed by Maurice Rickards. London: Evelyn, Adams & Mackay, 1968.

Seekings, Jeremy. The UDF: a history of the United Democratic Front in South Africa, 1983-1991. Cape Town: David Philip; Oxford: James Currey; Athens: Ohio University Press, 2000.

Seidman, Judy. Red on black: the story of the South African poster movement. Johannesburg: STE Publishers: South African History Archives, 2007.

South African History Archive. Posterbook Collective. Images of defiance: South African resistance posters of the 1980s. 2nd ed. Johannesburg: STE Publishers, 2004.

Timmers, Margaret. The power of the poster; edited by Margaret Timmers. London: V&A Publications, 1998.

Endnotes

[1] Maurice Rickards, Posters of Protest and Revolution; selected and reviewed by Maurice Rickards. (Bath, Somerset: Adams & Dart, 1970), 5.

[2] Rickards, Posters of Protest and Revolution, 6-11.

[3] Rickards, Posters of Protest and Revolution, 12.

[4] Rickards, Posters of Protest and Revolution, 16-20.

[5] Jeremy Seekings, The UDF: A History of the United Democratic Front in South Africa, 1983-1991. (Cape Town: David Philip; Oxford: James Currey; Athens: Ohio University Press, 2000).