by Leonie Twentyman Jones

Leonie Twentyman Jones was the Head of Manuscripts & Archives (MSS) Department in the University of Cape Town Libraries between 1975 and 1995. Her account provides insight into the experiences of an archivist in collecting and providing access in the troubled context of the times. She formed part of the larger unit within the Libraries who developed a significant body of research resources reflecting the activities of individuals and organisations working to oppose apartheid policy.

The horrific sight, on national TV, of flames devouring the UCT African Studies Library and many of its collections, followed shortly by photos and videos sent by former colleagues and friends in Cape Town — on a Sunday afternoon in April 2021— will remain with me forever.

Much has been written by those involved in the remarkable and ongoing salvage operations of the collections as well as by researchers mourning the loss of the beautiful building space which housed the library and created an area so conducive to research.

For those of us who acquired, catalogued, sorted, made available and cared for those collections in the past, but were unable to assist physically in their salvage, there has been time to reflect back and now to share a few memories from those times.

To me, building spaces, however beautiful and comfortable, are not the heart of a library. I have experienced at least 5 different physical spaces on the UCT campus where the African Studies Library (ASL) and associated collections have been housed – all of them different, but special in some way.

Starting with my student days when the nucleus of the collections was housed in a tiny area behind a wire fence at the top of the Jagger Library called ‘Stackroom 10’, with only 2 staff members and a handful of small tables where researchers could work in rather cramped conditions; to 1995 when I left UCT, when the ASL cluster was housed in copious accommodation, comfortable for researchers and library staff, with temperature-controlled storage areas, access to an in-house Conservation and Restoration unit and a staff complement of about 20.

I believe that all those areas were special and conducive to research for two basic reasons. Firstly because of the wide-ranging collections which were continually being added to; and secondly because of the dedicated staff who worked there, and their intimate knowledge of and care for the collections. All who worked there were conscious of and followed the example of the ‘pioneer’ librarians of the 1940s and 50s who recognised the importance of providing a true research library which grew and changed according to the research interests of staff and students as well as the political, economic and social conditions of the times. I am certain this continues to be the case today, and no matter where the Library is housed it will still be regarded with huge appreciation because of the quality of its collections and its staff.

The mid-1970s to mid-1990s was a time of change and turmoil on many fronts in Cape Town, the Western Cape and indeed the whole country.

(All Things UCT Collection, UCT Libraries Special Collections )

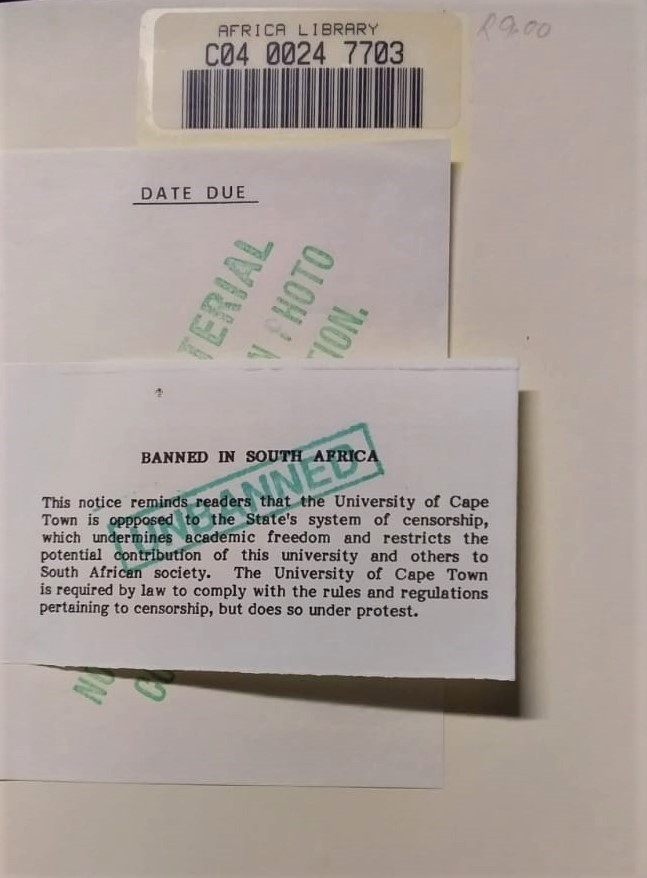

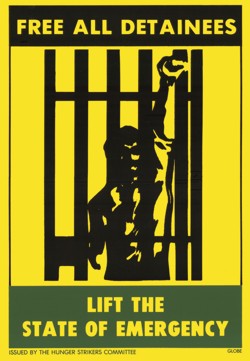

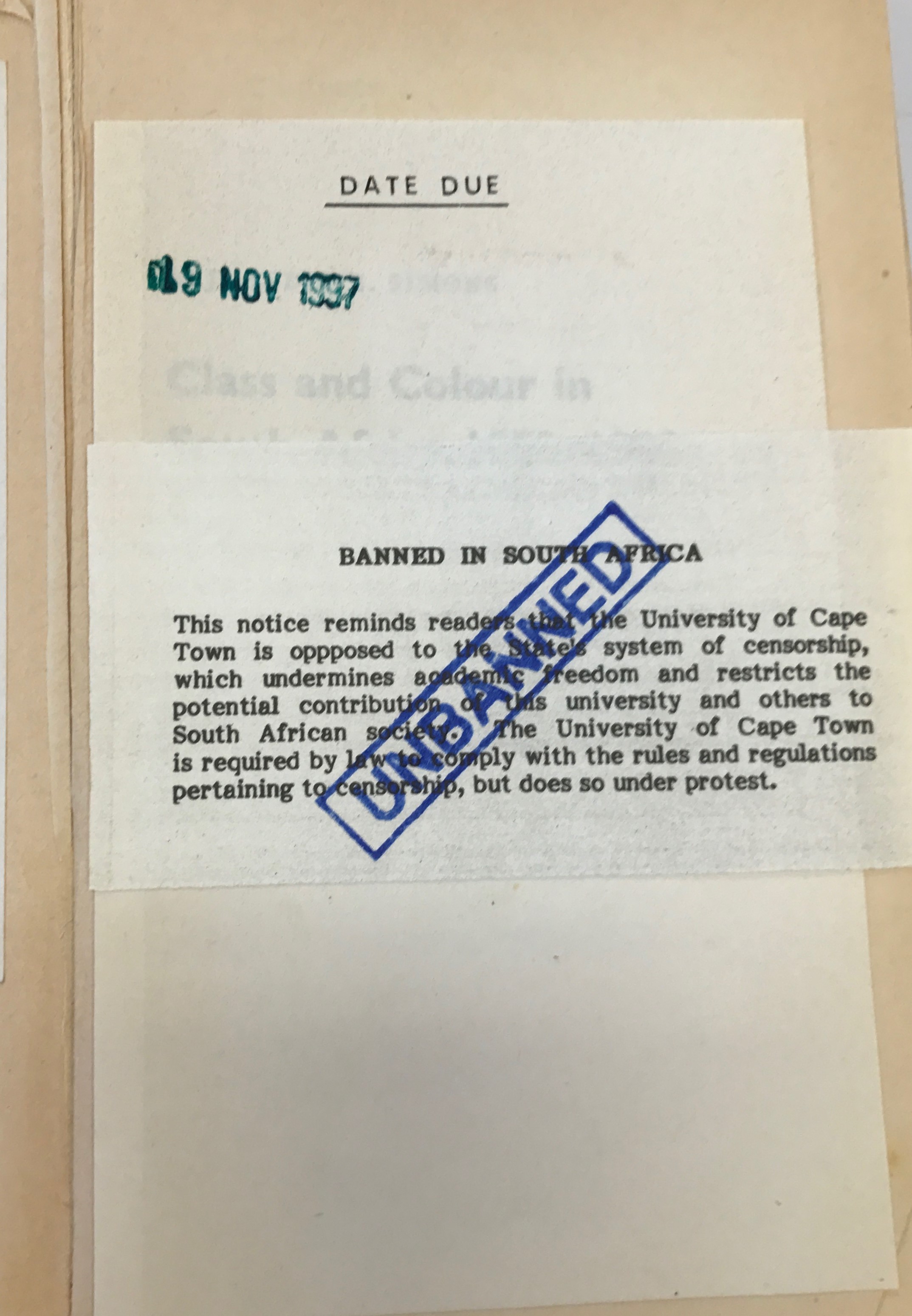

Some of us felt that the papers (minutes of meetings, correspondence, reports etc.) and publications created by organizations working for change in our society were under threat – either by confiscation or from destruction by opposing groups. Ephemeral pamphlets and video material were also important records of the times. For these reasons we librarians and archivists felt an urgent need to make available a safe environment in which such material could be preserved so that future generations could study all the different factions which operated during those troubled times.

Through discrete contacts with academic staff, the Centre for African Studies, student activists and other concerned individuals it became known that UCT Special Collections (ASL, MSS, Govt Pubs & Rare Books), firstly under Pam Stevens and then with greater urgency under her successor Margaret Richards, could provide a safe haven for such material. Some of the organizations were viewed by the State as a threat to the stability of the country, and therefore the State went to great lengths to negate this threat by intimidation, police raids, banning, detention and arrests, as well as infiltrating their own spies into such groups. It was known that some students had been recruited by being promised that their University fees would be paid for by the Security Police. The extent of police intelligence infiltration into a major student organization and its tragic consequences only came to light some years later.

When a valued member of our own staff was served with a 5-year banning order which prohibited her from coming onto campus and thus prevented her from working in the Library, we were made even more aware of the intensity of the problems facing us all.

The acquisition of the documents and publications of these organizations had to take place in rather unconventional ways and with a strong element of secrecy and a fair amount of anxiety. Documents were often received in batches via anonymous individuals, on the run from the police, carrying backpacks or carrier bags full of documents. A body of photocopied material arrived in batches from London over many months – sent anonymously through the ordinary post and looking like rolls of newspapers or journals. Imagine our delight when the faithful despatcher was able to return to SA after 1994 and introduce himself to us. Only a few staff members were involved in the receipt, accessioning, sorting and storing of such material. We decided to keep the storage boxes, with their innocuous-looking labels, hidden in ‘plain sight’. If questioned about such collections it was sometimes necessary to deny all knowledge of the material until the researcher could be safely identified.

One such donation was brought in by a man who was a bit older and far better dressed than the average student at that time. On being questioned as to why he had decided to bring us the extremely sensitive material, he gently said, ‘I know it is safe, I used this Library when I was a student.’

Academic staff lodged their research projects, some of which involved, for example, evidence of police brutality with regard to the treatment of detainees. Again access had to be carefully monitored.

On one occasion, excessive care led to an embarrassing situation, when I did not recognise the name of an eminent Johannesburg attorney who needed access to his detained client’s papers. I therefore denied all knowledge of the papers which I knew were quite safe in tin trunks stored at the back of the most distant strong-room in the Library. All was corrected when the rather bewildered attorney, dressed in a flowing trench-coat and looking like a character from a John Le Carré novel, was identified by a trusted member of the academic staff.

Secret contingency plans had been made by those of us involved in case of police raids, arrest or detention, but luckily these were not needed. One Friday afternoon I watched an example of police brutality play out right in front of the Manuscripts Dept (at that time on the northern side of the then Jameson Hall), as they invaded campus to break up a peaceful student protest. Tear gas was fired indiscriminately and students were chased and beaten with rubber quirts.

(All Things UCT Collection, UCT Libraries Special Collections )

Bomb threats to various campus buildings were a fairly regular occurrence at that time, usually on rainy days, requiring us to evacuate and stand in the rain waiting for the All Clear. Of course a bomb threat could never be ignored, but nevertheless was an unsettling and distracting process – wasting time unnecessarily.

Another collecting focus at this time was large organizations like trade unions. These contained letters written by workers in a variety of industries to their head office, describing working conditions, harassment by police and their hopes and needs. Such information is not available anywhere else. Papers had to be gathered from often cramped and dusty storerooms in mostly old buildings throughout Cape Town. Sometimes the papers were stored in amongst a variety of objects no longer needed by the organization, like a rusty bicycle, old furniture, equipment etc.

We were proud to have created a safe haven for the preservation of collections like these and to know that they would be available to help future researchers understand the events of those difficult times.

The realisation now that these collections may have been completely destroyed or irreparably damaged by water is devastating. All the promises we made in good faith to anxious donors now seem hollow and inappropriate. Although destruction by fire is always at the back of one’s mind, the university seemed such a safe and secure environment with comprehensive fire protection, and we had no cause to believe that the collections would not be safe.

The destruction of a Library or Archive, be it deliberate or random, means the loss of identity and memory of a people and their various cultures, without which there can be no understanding or remembering of the past or an ability to move forward to a better future.

Leonie Twentyman Jones

Knysna

October 2021