by Daniéle Knoetze (UCT Conservation Unit)

with contributions by Nancy Child, Lena Krahe, Karen Studniarz, and Celina Zenker

A new Conservation Unit has been established at UCT Libraries’ interim recovery premises in Mowbray. The unit is headed by senior conservator, Nancy Child, who brings with her expertise and decades of experience in art conservation, mycology research (the study and treatment of mould), and heritage conservation education. She is supported by junior conservator, Daniéle Knoetze, a recent graduate of the University of Pretoria’s Tangible Heritage Conservation Programme, who outlines below some of the work of the unit to date.

Why it’s important to conserve paper objects

Our memories and our histories, I would argue, depend on the visible, the archival and the material things that record and preserve a society’s life. Books, photos, and posters (to name a few) hold within them the power to retrieve individual and collective experiences. I feel that this is a good enough reason for us to treasure our paper objects for ourselves and future generations.

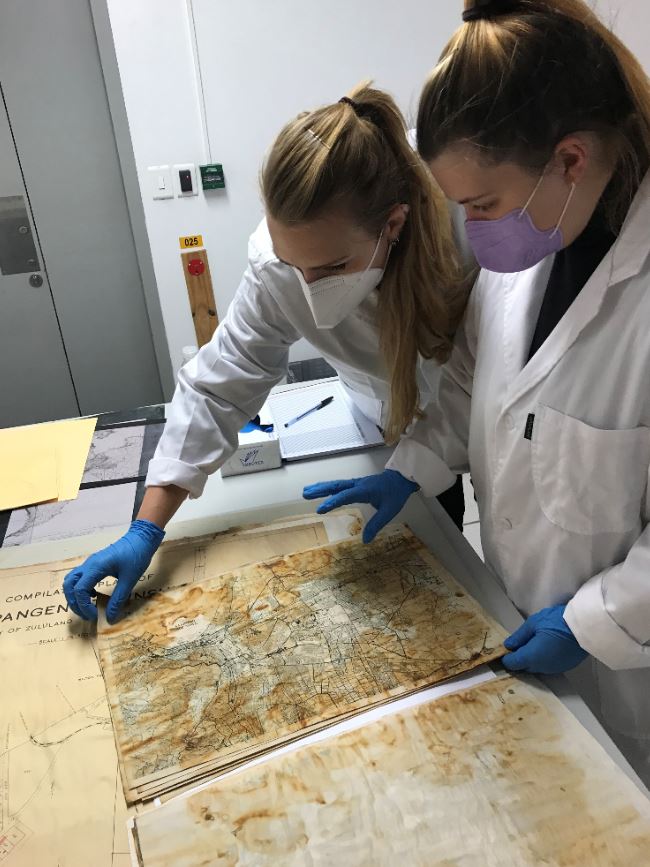

I had the privilege to work with Lena Krahe, Karen Studniarz, and Celina Zenker from the Cologne University of Applied Sciences from the 1st of September 2022 to the 30th of September 2022. They joined our unit as part of their internship for their BA Course in Conservation of Cultural Property. The past few weeks have been extremely rewarding and I feel that I should share my experience and give you a glimpse of a few things we did. I am sure you will find it just as interesting and informative as I did. I would like to take you on a journey of what a day in a paper conservator’s life looks like. What follows is a brief overview with visual references of what we did, starting with the documentation, through to the stabilising and treating of the object.

Development Goal: Condition report

The first aim was to develop goals for the conservation unit, which included documentation. We developed a template for a condition report form specially aimed at the objects found within UCT Libraries’ Special Collections, salvaged from the Jagger Library last year.

Documentation is an integral part of conservation: it establishes the condition of the object and helps in the decision-making process. This step shows other conservators our work steps and the materials which we used which in turn will help future conservator when returning to the object. The visual examination informs the decisions regarding the treatment options. Conservators should always keep the object’s condition, history, significance, and uses in mind before any decisions are made.

Know your materials

When dealing with different paper objects research should be done on each project. This assists in understanding the specific nature of the material. Each material reacts in different ways, and this should always be considered. Therefore, trained conservators with experience are so vital for institutions like UCT if we wish to safeguard our heritage.

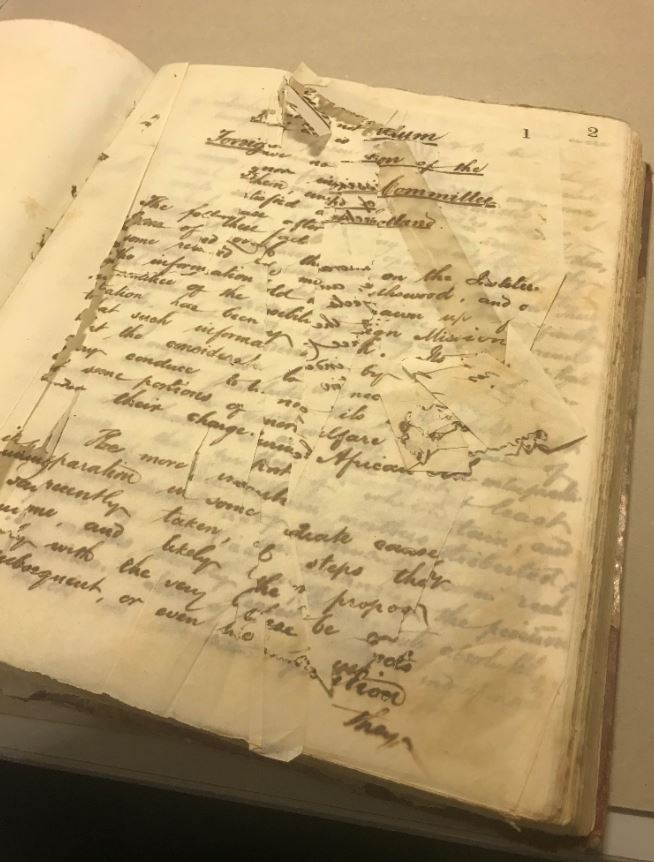

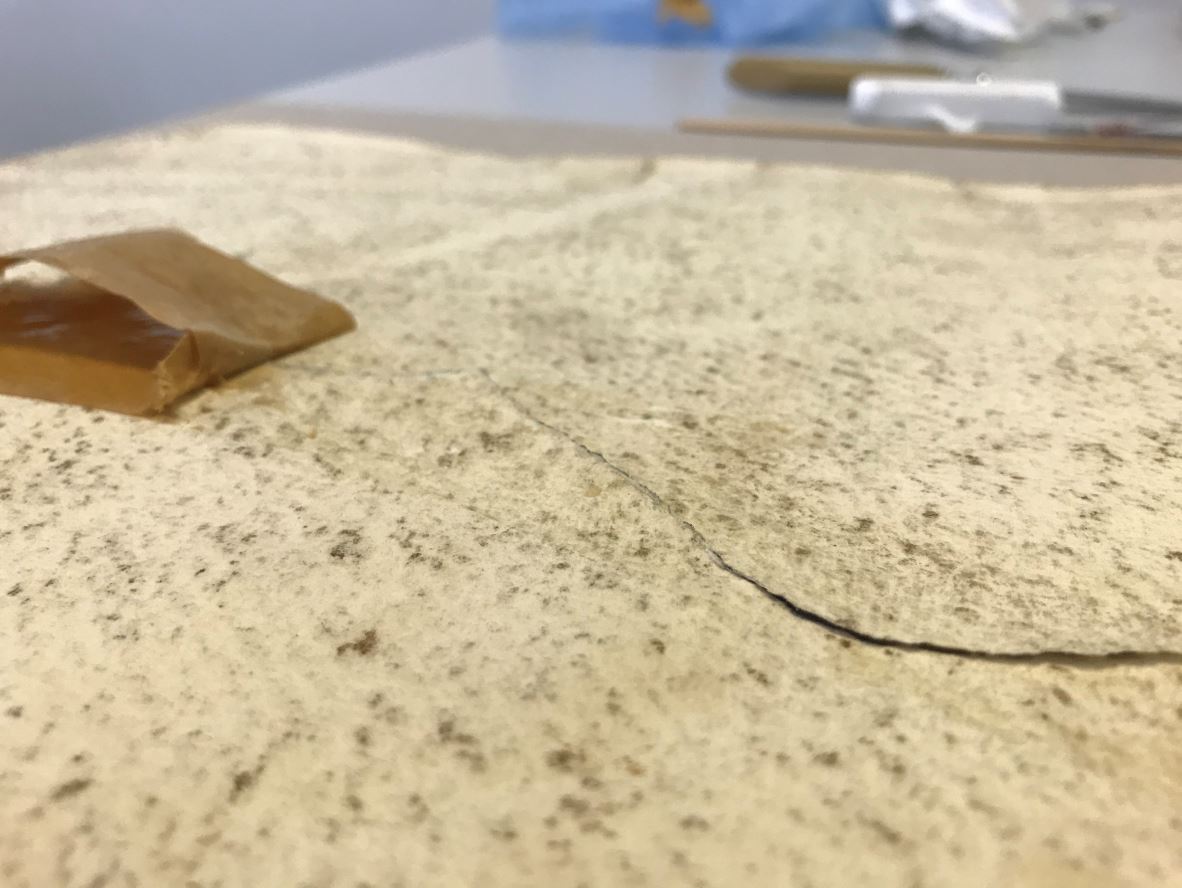

One of our projects made the importance of understanding the materials clear. The deterioration of paper by iron gall ink is a result of oxidation and hydrolysis reactions. This reaction is called iron gall ink corrosion, with the appearance of the ink burning through the page.

Generally speaking, the treatment of paper has many different aspects, depending on the condition and type of the paper itself. This can range from dry cleaning with a brush or sponge, to mending tears with wheat starch paste and Japanese paper, or even washing paper.

Having the right tools and materials are important, but they are sometimes difficult to get ahold of. Therefore, getting creative is the name of the game. Conservators usually pull from all sorts of different fields to find just the right tool for the job.

Here is a list of some of the basic tools you would typically find in a paper conservator’s toolkit:

- Bone folders

- Spatula

- Tweezers

- Scalpel

- Brushes

- Dental tools

- Tape measure/ruler

From documentation to stabilisation

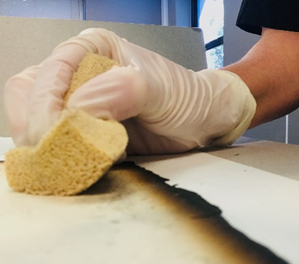

The next step after documenting the object is to clean its surface – this is referred to as dry cleaning (or mechanical cleaning)

After documentation, the next step is to get rid of all the surface dust and dirt. This can be done with a variety of tools, in this case we used soft brushes, a vacuum machine, smoke sponges and a microfibre cloth.

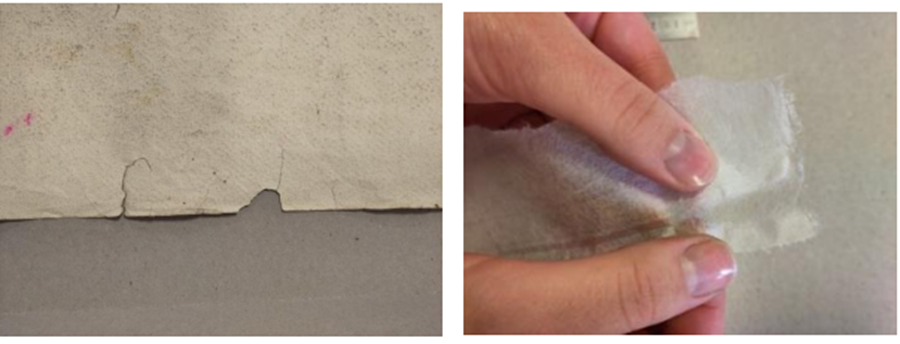

Removal of tape and tear mending

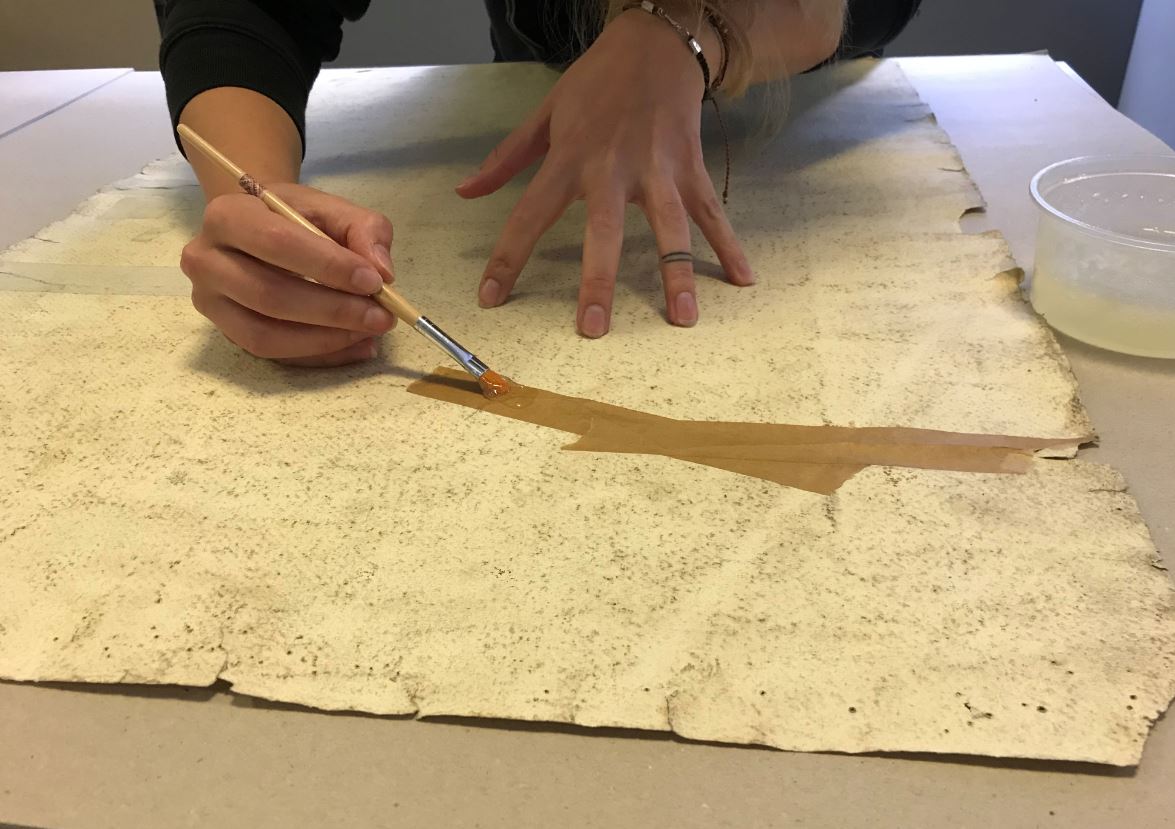

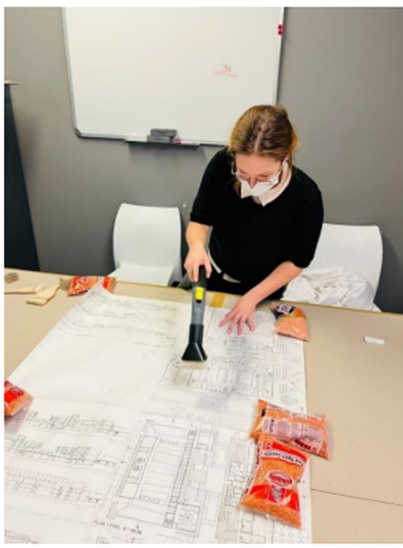

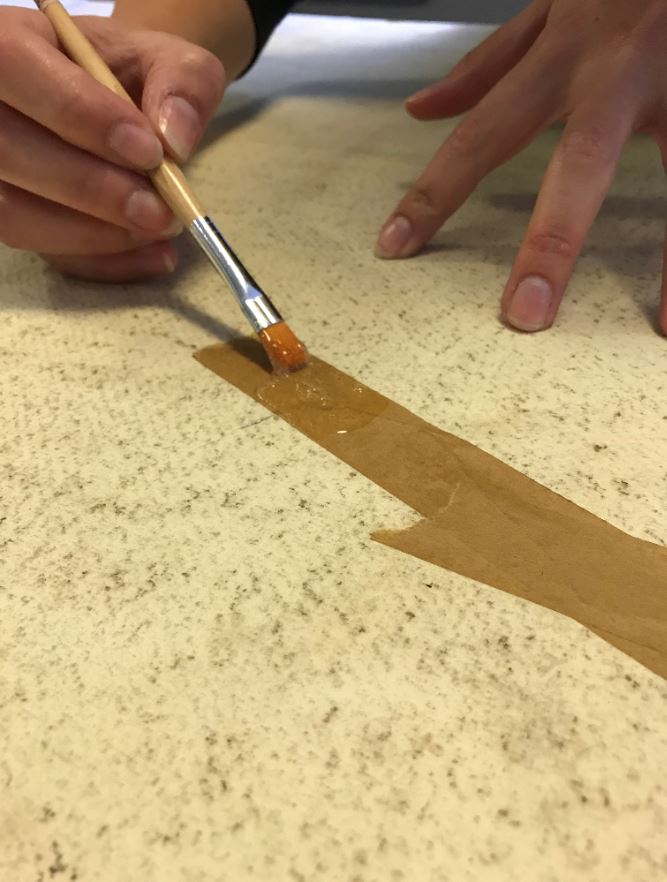

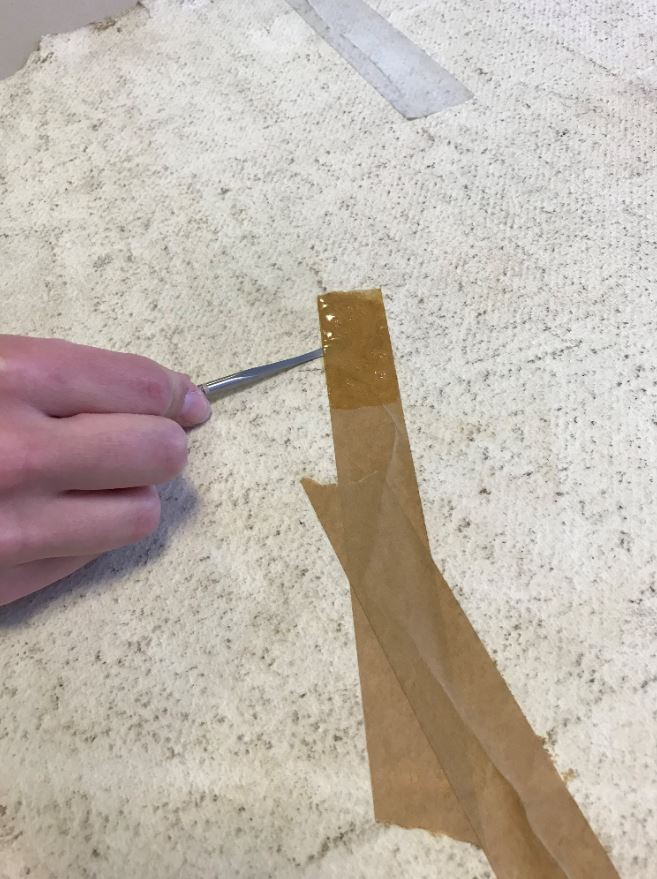

Some of the foreign materials, in this case tape, found on the objects cannot be removed with dry cleaning methods and the next step is to consider different wet cleaning methods. Because we are adding materials to the objects this must be an informed decision, not taken lightly. Another of our projects included the removal of various tapes off oversized posters. The paper is fragile so caution must be taken. The tape was covered in methylcellulose with a brush.

After waiting a few minutes, the tape was removed with a spatula. Conservators must implement treatments that can be reversed without damaging the original material of the object. The goal is not to simply make an object look ‘new’ for aesthetic purposes. Appropriate treatments take all technical, historic, scientific, cultural, religious, and aesthetic aspects of an object into account.

Wet treatment

Washing paper is usually a technique used to deal with stains, dirt, and discoloration of paper objects. The acidic nature of paper causes embrittlement and in return the object becomes more fragile. However, it is important to do a spot test and see whether the object is water sensitive.

Adhesives

The adhesive we chose was wheat starch paste as this is a common adhesive in a paper conservation lab. As wheat starch is not too difficult to come by (unlike most conservation materials) we purchased it from a local supplier in Rondebosch. The experimentation led to a comparison and discussion of the adhesives’ characteristics. The main goal is to have an adhesive with a smooth but firm, homogenous, and slightly translucent quality.

Tear mending: Japanese paper

Japanese paper is one of those materials you cannot do without when it comes to paper conservation. The strong and archival benefits of Japanese paper have been proven over time. Different scenarios that a conservator might be faced with needs different approaches, such as interleaving and surface repair. Ultimately, the goal is to restore the structural integrity of the object.

Problem Solving

Problem solving is a big part of conservation. Finding creative ways to solve challenges is the name of the game. An example of this is the need for proper weights. After tear mending, the area must be placed under moderate, uniformly distributed pressure. Making improvised weights can solve a common challenge when treating oversized paper material. Using bricks, small stones, or bags filled with either sand or lentils are some of the ways in which this challenge can be solved.

Playing with pigments: Inpainting on oversized paper objects

Inpainting on areas of surface losses and abrasions must be done with careful consideration, with the aim to make the damaged areas seem less distracting. This can be accomplished through choosing the correct medium (usually watercolour, acrylic, gouache, pencil, or pastel).

Through working closely with the interns for the last couple of weeks, I have come to realise that there are numerous different approaches when it comes to the treatment of paper objects. This makes a collaborative effort such as this incredibly valuable. It creates a dialogue between conservators, and it facilitates a space where knowledge and ideas can easily be shared.