written by Nina Liebenberg

Nina Liebenberg is an artist, a curator, and a lecturer at the University of Cape Town’s Centre for Curating the Archive.

In April of 2019, four years into my PhD research, and about eight months before the very first Covid-19 case was detected in Wuhan, I presented a paper as part of the British Society for the History of Science (BSHS) Postgraduate conference in Cambridge. In it, I likened a small object, sourced from the Manuscripts and Archives department of the University of Cape Town to a virus - buried and dormant – locked up in one of the department’s strong rooms. In making a case for this object’s viral characteristics, I outlined its problematic colonial history and questioned its relevance within an institution which has, since 2015 and the RMF movement, heard stringent calls for decolonising its curriculum. In a bid to reconsider this object (which is representative of many object collections in the university), I proposed the methods of curatorship and artmaking, as possible tools with which to convert this object into a vaccine instead, able to perform a healing function in the institution. At the time of writing, it is two years since I delivered the paper and exactly a year since the first official day the South African lockdown was initiated by President Cyril Ramaphosa to curb the local spread of the virus. In this single year at least 52 129 South African have succumbed to the virus, part of the 2.71 million deaths recorded worldwide. Nearly half of the world’s 3.3 billion global workforce are at risk of losing their livelihoods, and tens of millions of people are at risk of falling into extreme poverty. This is the paper, as I presented it almost two years ago…

Between 1890 and 1941, there was a certain type of object that could boast of travelling

up the highest mountain peaks on Earth,

and down to its snow-covered southernmost tip.

circumspect the globe,

and traverse the largest expanses of ocean.

Taken on hunting trips by a president, and used to treat a Queen, it was a firm favourite amongst believers in God – or those who would rather put their faith in imperial power.

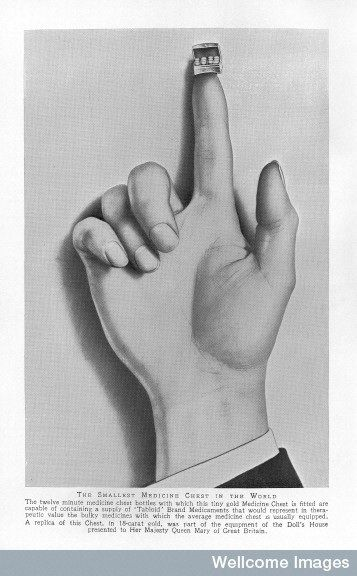

It travelled by plane, by sledge, by boat, by hot air balloon, and could be strapped to a horseman’s saddle, clipped to the handlebars of a bicycle, or slid into a shirt pocket or under the seat of a car. One could even be precariously balanced on the tip of a finger.

It withstood being submerged in swamps, being struck by lightning and was owned by explorers such as Stanley, Amundson, Mallory, Scott and Shackleton, and requested by army generals, international news correspondents, and missionaries alike.

On the 3rd of November 2018, one of these objects appeared in an exhibition in the Iziko South African Museum. Roughly 15cm in height and depth, and 20cm in width, it is made of metal and painted black, with the words ‘Trade Mark’, ‘Tabloid’ and ‘Brand’ printed under the keyhole, on its front. Fitted with a brown leather strap and metal clasps, the case suggests easy portability and containment. Opening it reveals two layers, the top one filled with an assortment of bottles, paper packages and instruments, whilst the bottom one is more regimented and has 16 compartments filled with glass bottles of roughly the same size. Labels read ‘Chlorate of Potash’, ‘Quinine and Cinnamon’, or ‘Opium’ to name a few, and each lists a breakdown of the compounds and directions for use. The chest also contains a ‘Tabloid’ guide which lists the various medicine cases and their applicability to different journeys and destinations, as well as common ailments and their treatments. At the back of the box, inside the lid, an oval copper crest reads ‘Burroughs Wellcome & Co, London’.

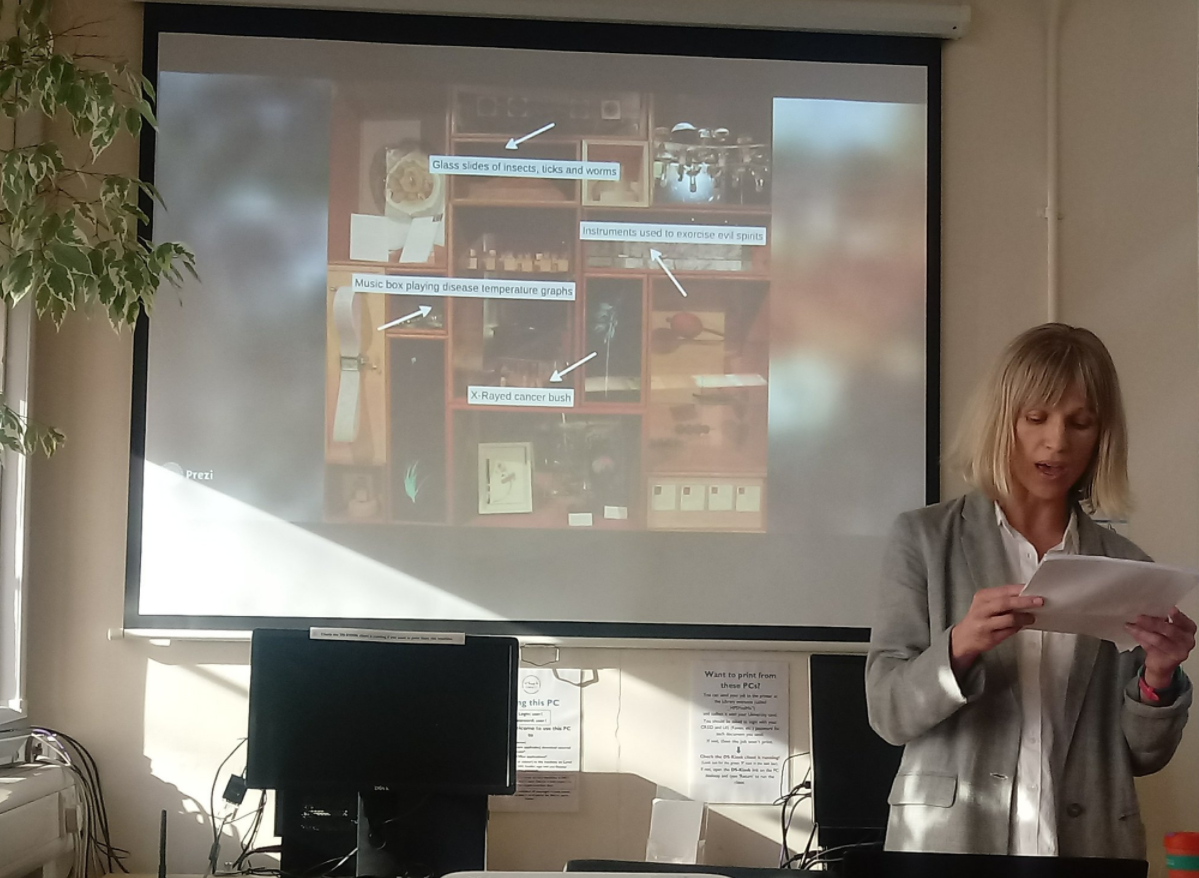

In the cabinets that surrounded the medicine chest, there were a vast array of artworks and objects sourced from various University of Cape Town departments. In the top centre cabinet, a collection of glass slides showed various insects, ticks and worms that are the primary or intermediate hosts or carriers of human diseases, whilst the cabinet in the bottom right, housed three instruments used in healing rituals to exorcise evil spirits. In a cabinet on the left, a hand-cranked music box played the temperature graphs of malaria, yellow fever, trypanosomiasis and tickborne-relapse fever, and a few cabinets to its right, an X-rayed indigenous cancer bush specimen was displayed.

It is however the object that sat at the centre of this cabinet, the No 254 Wellcome Burroughs and Company medicine chest that forms the focus of this article and my PhD research.

The 2018 exhibition was one in a series of exhibitions, which explored the object’s ties to the history of imperialism, colonialism, disease and local medical practices. It investigated a variety of ways in which interdisciplinary enquiry (as method) can potentially illuminate and contest the colonial narratives of the chest, and how curation, as a practice which facilitates interdisciplinarity, can provide a framework in which these polyphonic dialogues can exist, and prompt further discussion.

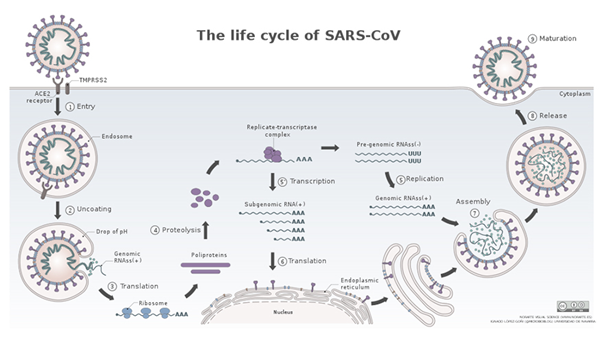

I have employed two different strategies for viewing the object: as a virus and as a vaccine. A virus enters a host and uses its cells to replicate itself. A vaccine is a weakened version of the same virus injected into a body in order to activate the production of anti-bodies in order to combat any future attacks by a similar agent. (Or, as the new developments prompted by Covid-19 research has shown us, relate instructions to our own cells to manufacture cells which replicate the virus in order to build defenses against it). Throughout this whole process, the chest and my activities as curator will reflect the various qualities and characteristics of these two medical terms.

The chest as a virus materialises through its history and ties to the colonial project. Burroughs Wellcome & Co (from here referred to as BWC) was established in 1880 by Henry Wellcome and Silas Burroughs. The company manufactured a wide range of pharmaceutical products, which included medicine chests. Made of resilient materials to withstand a range of climates and environments, their contents (which included dressings, simple surgical tools and medicines) were lightweight and easy to transport over long distances.

(Source: Wellcome Library, London)

As a consequence of Wellcome’s business acumen, personal contacts, and interest in exploration and missionary work, examples of the company’s chests were used as part of heavily promoted overseas expeditions throughout the British Empire and beyond. As alluded to at the beginning of the paper, Henry Morton Stanley used specially made chests on his missions in Africa between 1887 and 1890, and a chest accompanied mountaineers attempting to scale Everest in 1933 and was also numbered amongst Scot’s equipment during his pursuit to reach the South Pole in 1910. At the end of these expeditions, the chests were featured as tools of travel and exploration within company brochures and through their display at international trade fairs.

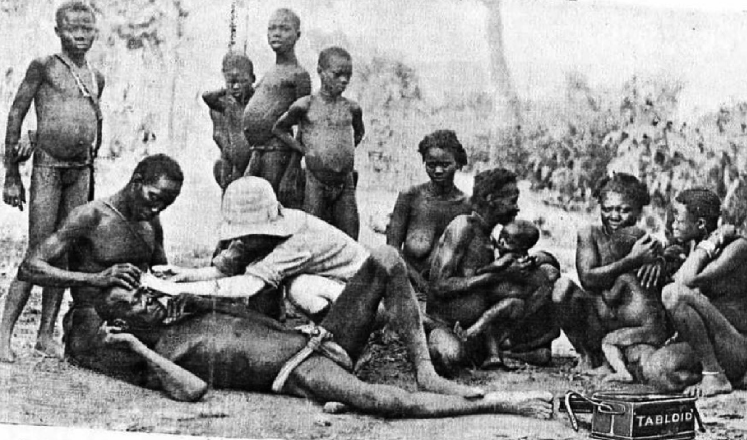

Often pictured alongside white Europeans, Tabloid medicine chests became standard equipment for scientists, and medical practitioners working in the tropics. Western medical intervention was often portrayed as an important first contact within this space, and BWC promoted the Tabloid brand medicine chest as going “hand in hand with the advance of civilisation, the conquest against disease and the battle against ignorance and superstition” (1934:27). Drawing on the work of Edward Said, historian David Arnold (1996, 2000, 2006) has noted how the tropics were understood as both a specific geographical location, as well as a conceptual space – something culturally and politically alien, as well as environmentally distinctive from the west. Western language describing tropical climates was saturated with words such as “paradise, plush, and bountiful, alongside danger, disease and darkness” (Arnold in Johnson 2008: 258). BWC (1934) reinforced the image of the tropics as deadly and disease ridden: “A danger far worse than that of broken limbs, of cuts and gun-shot wounds, hangs over the traveller in remote places, particularly in the Tropics. The worst menace he has to face is disease”, the company noted in one of its publications.

In order to face said multitude of dangers in an area which was then known as Northern Rhodesia, a particular chest was hand-picked off the BWC shop in 5 Loop Street, Cape Town in 1913 by Walter Floyd, a dentist born in Kent, who opened a practice in Cape Town in 1904. It travelled with him on both a hunting trip to (then) Northern Rhodesia and to German East Africa, where he was stationed during the war – both of these locations falling with the tropical coordinates. I would venture that Floyd would have identified with BWC’s narratives of the hunter, the doctor and the explorer – and its marketed associations with the chests.

Looking at the history of these chests, one can start identifying a viral pattern. Manufactured in the empire, it travelled into the colonial outposts, was picked off a shelf and then taken up into the interior of the continent where throughout this journey, it embodied certain ideas of the empire, infecting and spreading these ideas, which undermined the local medical practices even as these were appropriated. The historian Daniel Headrick (1981:72) attributes the ‘penetration of Africa’ to the development of technologies that supplied European imperialists with both the means and the motivation to pursue aggressive colonisation and push further and deeper into Africa – acquiring land and resources.

Similar to a virus hijacking a cell’s DNA factory in order to produce its own, BWC did not hide the fact they frequently found inspiration from local practice. Many if not most of their medicines were derived from outside Europe, and had been in use for decades, if not centuries (Johnson 2008: 261). They triumphantly acknowledged how certain drugs were developed through “observing locals”, and that the real benefits of such remedies were only truly discovered when they had been “recast through western science” (Ibid.). Prior to this BWC infection, the diverse population of the Cape Colony consisting of indigenous Africans; Khoekhoe; San; slaves from the East Indies, and their descendants; Dutch-Afrikaners descended from Dutch and German settlers; and British settlers, resulted in the growth of a Creole folk medicine. This growth troubles the view of indigenous bodies of knowledge as static, unscientific and irrational and argues that they are instead dynamic and continually evolving through their interaction with other medical systems. Historian Karen Flint (2008) notes how in early encounters between Africans and white colonists there was room for exchange between the two cultures as African medicine helped save many Europeans who did not have experience with local illnesses, while the medical expertise of missionaries facilitated the setting up of mission stations. During these interactions European medical practitioners adopted practices and remedies from African medicine and respected African healers. Similarly, African healers incorporated European remedies and certain medicines into their therapeutic practice. With the introduction of biomedicine, of which BWC was the main proponent, the medical landscape changed, and a superficial line was drawn between ‘indigenous’ medicine, rendered as ‘primitive’ and ‘unscientific’, and western medicine. The chest as virus does not only exist in the narrative of its history, however.

When it is not being exhibited, it lives in the archives of the University of Cape Town. As part of an institution that has sworn dedication to de-colonising its curriculum, it poses a somewhat latent threat. In a speech in 2011, the writer and former black vice-chancellor of the University of Cape Town, Professor Njabulo Ndebele, stated that “there can be no transformation of the curriculum, or indeed of knowledge itself, without an interrogation of archive” (Ndebele in APC 2019). An argument which strongly suggests that a critical assessment of the archival legacy on which the institution is founded becomes of pivotal importance to re-imagining a decolonial institution.

What worth then, if any, does this object serve in a new curriculum? In this specific UCT archive it still functions as a virus, perpetuating a Western hegemonic narrative, along with most of the other archival objects that also share this space. Is it possible to vaccinate ourselves against this presence?

During the last 5 years, the material remnants of colonialism has started disappearing off the University of Cape Town campus, from statues being removed, to artworks being burned. The question of what to do with these markers of oppression has been heavily debated – and the debate still continues.

As a lecturer and student in the Michaelis School of Fine Art department and specifically one in the Centre for Curating the Archive research facility, the practice of curatorship offers interesting avenues to explore in regard to these issues. Active curatorship enables and celebrates diverse interpretations of objects – in many instances deflecting attention away from objects onto the systems that gave rise to them in the first place. This method offers a means to challenge existing hierarchies and knowledge production through the formulation of imaginative strategies in relation to historical material.

As an artist and curator, my practice centres on dialogue and multidisciplinary exchange with experts in fields ranging from chemistry, physics and engineering to medical imaging and botany – focusing on illuminating the layered, and interconnected relationships between sets of ideas and objects sourced from these various disciplines. The curatorial space offers me the means to materialise these layered and interconnected connections.

In considering this history, I started seeing the potential for taking the chest virus and converting it into a vaccine. As stated before, most vaccines consist of elements of the actual virus albeit in a weakened state, which is injected into a body in order to generate defences against said virus, should one of these try entering the body at any point in the future. In terms of the chest virus, I therefore needed to develop mechanisms through which to weaken its current state, in order to use it as an agent that would encourage a reaction in the institution and beyond. Drawing on interdisciplinarity, my first tactic consisted of weakening its perceptual boundaries through reconnecting the chest to various disciplines within the university for examination.

Perspective implies the subjective nature of knowledge and the situatedness of the knower (through its implicit visual-spatial metaphor). It can refer to ways of thinking based on one’s subjective outlook, opinion, beliefs, or knowledge; or to that which might be common to a class of individuals in shared situations, roles or relative positions. In a third sense, it can refer to “a way of seeing and thinking that is based on a commitment to a system of theories, a body of professional knowledge, a discipline, or a discourse community. It describes seeing the world through the lens of assumptions, concepts, values and practices of shared ways of knowing” (Miller & Boix-Mansilla 2004 :3).

What we see (and just as importantly, what we do not see) is determined by these unfolding frameworks that pre-organise or predispose the empirical reach of our perception. Disciplines illustrate the limit of this reach – and how this limit varies contextually, very effectively. Taking all this into account, the chest, as viewed from each individual discipline, would potentially start occupying a weakened state within that viewing session, since the single disciplinary perspective invariably excludes a variety of its other characteristics and negates its fullness. These disciplinary views also separate out and distil individual characteristics of the chest, which counters the idea of the chest as a powerful whole. As such, in this impoverished state, the chest virus starts acting as a chest vaccine and allows the discipline to attack it in various ways – generating counter-narratives to its colonial viral history.

It is this hypothesis that I set out to test at the beginning of this research, and it is these counter-narratives, which took the form of the objects, artworks and images, that made up the mobile set of cabinets, which occupied the space in the Iziko South African Museum.

The cabinets represented the various anti-bodies generated by the different disciplines, with a particular focus on the Botany department and materialised the decentralization of the chest, showing how it is one of many objects and one of many narratives. The disciplines reacted to various aspects of the chest: from its disavowal of local medicinal practices, to its evocation of illness and disease as a state that affects everyone. The influence of colonialism, as carried by the chest, became evident throughout: surfacing in invasive botanical species carrying foreign diseases, insect vectors introduced through expanded trade routes, or pathological specimens affected by typhoid and yellow fever, tuberculosis and malaria. In order to illustrate this, I will highlight a few of the cabinets, and their counter-narratives.

Two X-rayed indigenous plant specimens: the Bulbine and Sutherlandia frutescens occuped two of the cabinets. Used in the treatment of chicken pox, internal cancers, colds, asthma, TB, bronchitis, liver problems, heart disease and various other conditions, they create an indigenous botanical presence which stands in contrast to the lacunae represented by the chest. In presenting the chest to the Botany department it was noted that the botanical origins of almost all of the medicines present in this specific chest were from outside of Africa. A strange occurrence especially if one considers the long history of the Cape as a point on the trade routes where ill sailors regularly disembarked and drew on the knowledge of the Khoekhoe traditional healers for treatment and herbal cures (Laidler & Gelfand 1971). The Cape flora offered a plenitude of medicinal resources and these healers (who were skilled in botany, surgery and medicine) used them in a variety of healing practices (Viljoen 1999)

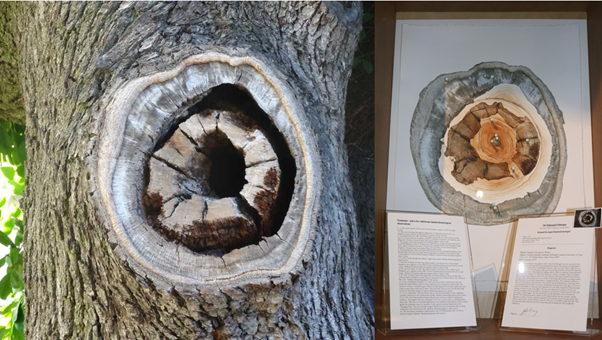

Highlighting the introduction of European botanical species into the local environment, is a work situated in the top left cabinet. The English oak was brought into the country by the early settlers and is believed to be among the first exotic tree species to be planted in South Africa, shortly after Van Riebeek’s arrival in 1652. In South Africa, oaks do not grow as old as they do in Europe. Because of the high temperatures, these trees grow faster than their species back home, and their centers start rotting over an extended period of time. The center part of the wood – the heart- is affected by this occurrence – and hollowed out over time.

Conflating medicine, history and botany, this ill English oak tree, planted in the 1830s on what is now the University of Cape Town grounds, was diagnosed by UCT dendrochronologist, Dr Edmund February. In an effort to treat this disease, I filled the absent heart cavity with paint I made by boiling the leaves of the Sutherlandia frutescens bush, which is an indigenous plant used locally for the treatment of heart disease.

Two individual cabinets relate to the chest’s interactions in the South African College of Music’s Kirby collection. The collection is a unique and irreplaceable assembly of more than 600 musical instruments, most of which were used in Southern Africa before 1934, many pre-dating urbanization. On encountering the chest, three of the instruments presented themselves, two gourd rattles and one iodophone. All three of these are used in Venda healing rituals to exorcise evil spirits.

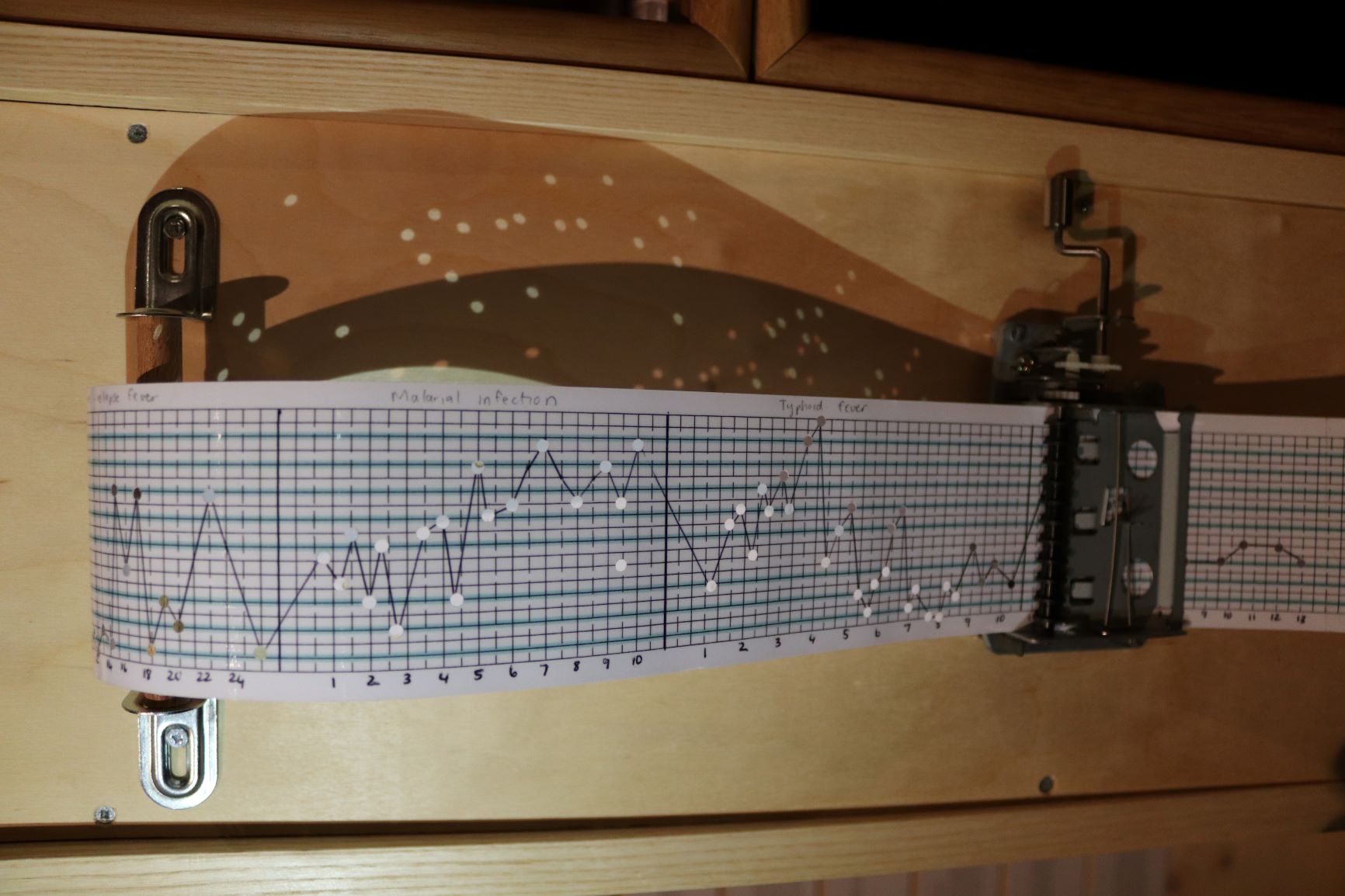

A second work draws on the history of music in Islamic healing practices. It shows the conversion of the temperature graphs of malaria, yellow fever, trypanosomiasis and tickborne-relapse fever – all fevers viewed as ‘tropical’ – into a musical score. The vertical axis represents the temperature variations and the horizontal one, the approximate number of days the fever is said to last. Since 1652, when the mentally ill were still being burnt alive in Europe, traditional Islamic medicinal practices included using music as a form of therapy to treat psychological illnesses. A 10-piece band would play different ‘modes’ to treat ailments from paralysis to palpitations in hospitals especially designed to include sounds of nature.

As a mobile unit, consisting of a variety of antibodies generated by the vaccine at its centre, something very strange happened as it was wheeled into the Iziko South African Museum on the 3rd of November of 2018.

Museums have played a significant role within the colonial project, framing objects through a mostly Eurocentric perspective and exhibiting them in displays that suggest a tightly woven narrative of progress and an “authentic” mirror of history, without conflict or contradiction (Marstine 2006). My mobile set of objects formed part of a bigger exhibition titled Object Ecologies consisting of four of these mobile museums created by staff and students of the Centre for Curating the Archive. Stationed at various locations in the museum, they countered the authoritative voice of the institution and pointed to the polyphonic nature of objects – drawing attention to their making, their circulation, and the issues at stake when they are moved from one place and time to another. As such, these units started functioning as viruses within their new home, presenting sets of ideas to infect the institution into considering its role as custodians of a vast collection of objects that need to be challenged on a regular basis in terms of its role in justice and restoration.

To end, it is quite interesting to note how most of the medicines in Walter Floyd’s chest was never used. It seems that it is only now, more than a hundred years later, that the chest is starting to perform its healing power – and that, against all odds.

View the Tabloid Medicine Chest on the CCA’s Object Ecologies’ Website

References

Arnold, D. 1996. Inventing topicality. In The problem of nature: environment, culture, and European expansion. London: Blackwell.141–168.

Arnold, D. 2000. ‘Illusory riches’: representations of the tropical world, 1840–1950. Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography. 21: 6–18.

Arnold, D. 2006. The tropics and the traveling gaze: India, landscape, and science, 1800-1856. Seattle: University ofWashington Press.

Burroughs Wellcome & Co. 1912. The application of science to industry: souvenir of the congress of the universities of the empire of London. London: Burroughs Wellcome & Co.

Burroughs Wellcome & Co.1934. The romance of exploration and emergency first aid from Stanley to Byrd. London: BurroughsWellcome & Co.

Flint, K. 2008. Healing Traditions: African Medicine, Cultural Exchange, and Competition in South Africa. Athens: OhioUniversity Press and Scottsville: University of KwaZulu Natal Press.

Headrick, D. 1981. The tools of empire: technology and European imperialism in the nineteenth century. Oxford: Oxford UniversityPress.

Johnson, R. 2008.Tabloid brand medicine chests: selling health and hygiene for the British tropical colonies. Science as Culture. 17 (3): 249-268.

Johnson, R. 2008. Commodity culture: tropical health and hygiene in the British Empire. Endeavour. Volume 32(2): 70 – 74.

Laidler, P. & Gelfand, M. 1971. South Africa: its medical history 1652-1898. Cape Town: Struik.

Ndebele, N.2019. Archive and Public Culture. [Online] Available: http://www.apc.uct.ac.za/researchers/professor-niabulo-ndebele/. 02/04/2019.

Miller, M & Boix-Mansilla, V.2004. Thinking across perspectives and disciplines. Boston, MA: Harvard Graduate School Education.

Marstine, J. 2006. New museum theory and practice:an introduction. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Viljoen, R. 1999. Medicine, health and medical practice in precolonial Khoikhoi society: an anthropological‐historical perspective. In History and Anthropology. 11(4): 515-536.

Nina Liebenberg has been teaching on the CCA’s Honours in Curatorship programme since 2013, facilitating their annual interdisciplinary workshops, using curation as methodology to explore various overlaps and connections between diverse university departments.

As a PhD candidate, her current research is focused on disciplinary object collections as covert markers of the colonial and apartheid regimes; and curatorship and artmaking as methodologies able to address these histories through uncovering and extending the meaning of these material depositories beyond their disciplinary scope.