*CRISPR technology: A tool for translational cancer research?

*CRISPR technology: A tool for translational cancer research?

Irrespective of your field of interest, I am sure that like me, you feel more than intrigued to explore novel technologies that claim to “revolutionise” the approach to cancer therapy. When the mainstream media and major leading journals reported on the CRISPR (pronounced “crisper”) gene editing technology at the end of last month, I found myself inclined to further understand what this could mean for research and more importantly how this could affect individuals with cancer.

Short for ‘Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats’, this technology gives scientists a tool to specifically target genes and make precise cuts in DNA. Compared with earlier genome editing, the CRISPR system enables researchers to edit genes more efficiently and 200-times cheaper.

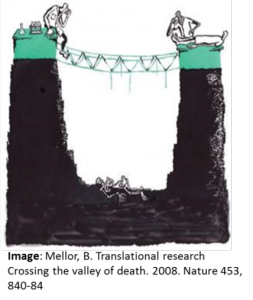

Scientists from the Novartis Institutes for BioMedical Research (NIBR) working in collaboration with the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard have started using CRISPR to study a large collection of cancer cells lines known as the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) to explore potential gene therapies and to identify drug targets. The questions I always find myself drawn to include: a) what does this means for patients suffering from cancer and b) how long will patients need to wait before this technology makes a difference to their lives?

Although it is difficult to approximate when this technology will be available in the clinical setting, we have already seen evidence that gene editing technology can be useful in treating people with cancer. In 2015, the high-profile story of Layla Richards (photograph below), a young girl diagnosed with leukaemia and then successfully treated with an experimental immune therapy at London’s Great Ormond Street Hospital brought to light the potential value of this technology. Although this was done using TALEN (an older form of the CRIPSR technology), many experts in the field of gene editing believe that the CRISPR might make this type of gene editing immune therapy more accessible and cheaper. http://www.macleans.ca/society/health/the-game-changing-technique-that-let-doctors-find-cancers-achilles-heel/

As researchers, the end goal of translating novel technology to patient care must be prioritised. One can only hope that harnessing CRISPR technology for cancer research will continue to bring together physicians, laboratory scientists, bioengineers, and epidemiologists to achieve future advances in cancer patient therapy.

What are your thoughts as scientist, public health specialists and clinicians on this technology? What do you think needs to be done to ensure collaborative translational research to bring about advances not only in research but also in patient care? Please share your ideas and suggest how the PhD mentorship group can set precedence in driving this agenda forward in our own research settings?

Image: Layla Richards, the first patient treated with genome-editing technology, at Great Ormond Street Hospital in London. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/health/news/11978250/Parents-who-refused-to-let-baby-die-of-leukaemia-change-medical-history.html

*Image: Illustration by Todd St. John http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2015/11/16/the-gene-hackers