Breast Cancer Prevention and Control Policy

By Trish Muzenda and Lelani Hobane

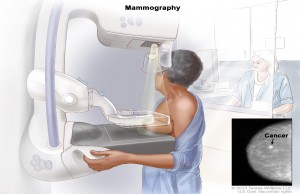

Breast cancer is the leading type of cancer diagnosed in women globally. Since 2008, the incidence of breast cancer has been evenly distributed globally, with 50% of breast cancer incidence occurring in the developing world. However of the total cases, approximately 58% of breast cancer mortality occurs in the developing world. Given these statistics, it is ever more important for governments in developing nations to take issues of breast cancer seriously and design contextual prevention and control strategies. In South Africa, the lifetime risk for breast cancer is 1 in 29. This risk is high and therefore requires that the department of health have guidelines that are there for screening of cases so as to improve diagnosis of breast cancer as well as treatment and rehabilitation following breast cancer diagnosis. To mirror the growing importance of breast health care in South Africa, the South African National Department of health has published a revised Breast cancer Policy brief as of June 2017. This policy outlines the guidelines to be used by all stakeholders towards health promotion, screening and treatment of breast cancer. Whilst the policy does touch on prevention of breast cancer, the backbone idea in the breast cancer policy of 2017 lies in improving the screening capacity for breast cancer.

Through the National Health Insurance (NHI) which is the central means by which the government aims to achieve universal coverage, the government is revitalising service delivery, changing the way that health services are financed, ensuring the provision of primary care, improving access to qualified human resources for health, and ensuring the availability of quality assured medical products. For the breast cancer policy, this can be seen in that much thought has been put into the use of all primary healthcare facilities as centres for the opportunistic education of women on general breast health including breast cancer risk factors. The policy also advocates for the education of women on how to practise Breast Self-Examination (BSE) and the importance of receiving a routine clinical breast examination (CBE). Additionally the establishment and maintenance of Specialised Breast Units set up in various tertiary level health facilities are to be used as referral points for suspected breast cancer cases for further diagnosis.

Source link: Breast Cancer Policy 2017.